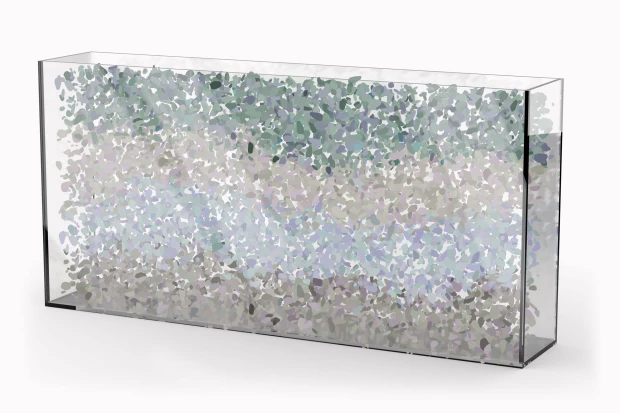

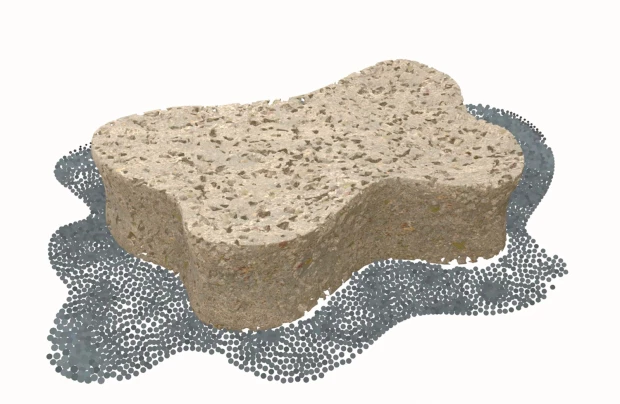

The way the subterranean world is perceived in popular imaginaries, also shapes how we understand, manage, and interact with this space. Aquifers are often misrepresented as static underground tanks—neatly bounded reservoirs waiting to be tapped (Ballestero 2018). This image is misleading. Aquifers are not rigid containers but dynamic, porous formations, more akin to sponges than tanks. The sponge is the aquifer’s architecture and mode of operation, embodying its fluidity, variability, porosity, multidirectional flow, and resistance to fixed boundaries.

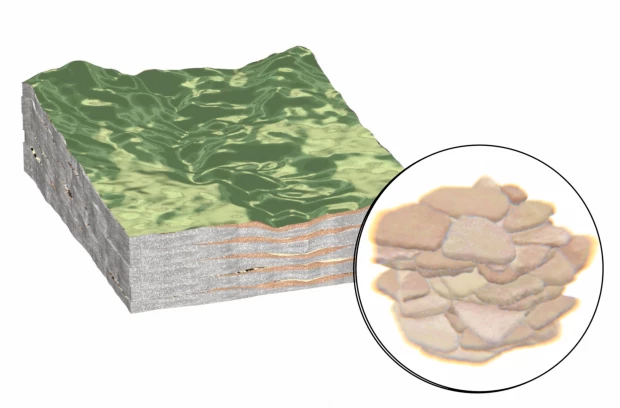

The tank imaginary does not come out of nowhere. Cross sections of the underground convey the space in a series of stratigraphic layers—solid, stable, and neatly divided, the aquifer embedded in these layers. But these layers are also materials, rocks and sediments which constitute different geological formations. Depending on one’s focus, water or rock could alternately appear as figure or background (Ballestero 2018). This instability reflects the aquifer’s nature—neither solid nor liquid alone, but a dynamic interplay of both.

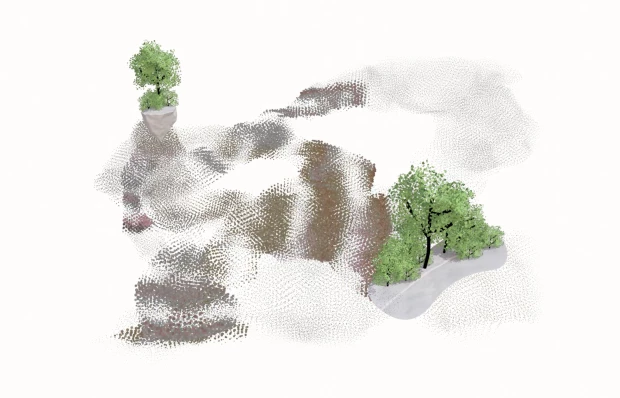

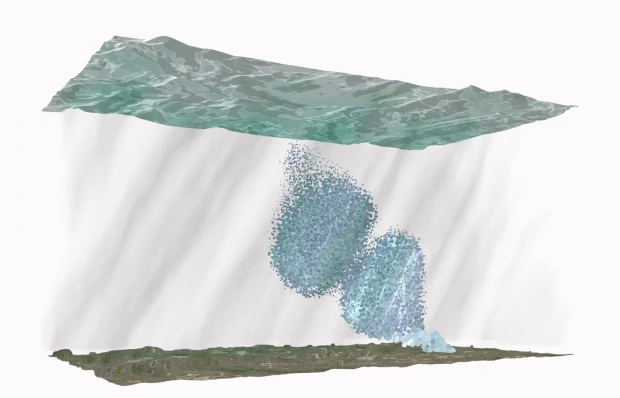

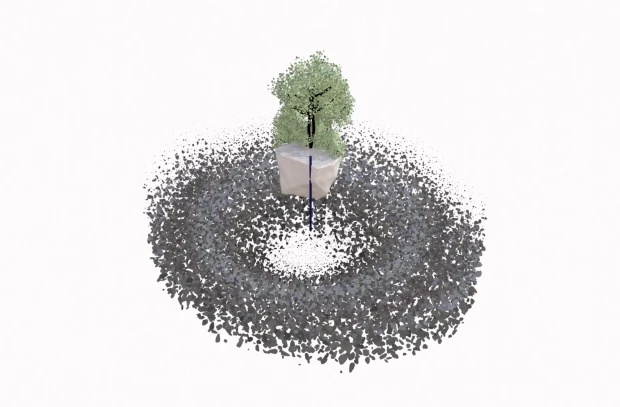

This shift from tanks to sponges is not just poetic but also politically necessary, as climate change is forcing the depletion of underground water. How should we visualize this complex architecture of diverse textures saturated with water?

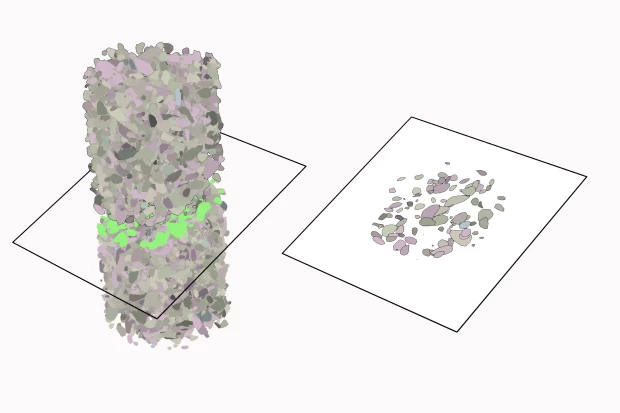

Aquifers, like sponges, are defined by the movement their pores make possible. Pores are irregular gaps within the solidified sediments and magmatic materials that hold and release water. Aquifers consist of permeable rock, fractured stone, and tiny gaps between sediment grains. Unlike a tank, which has a uniform structure, a sponge’s architecture is uneven—some parts absorb more, transport more, and others less. This variability means that water in an aquifer does not move uniformly but follows paths of least resistance, pooling in some areas while bypassing others.

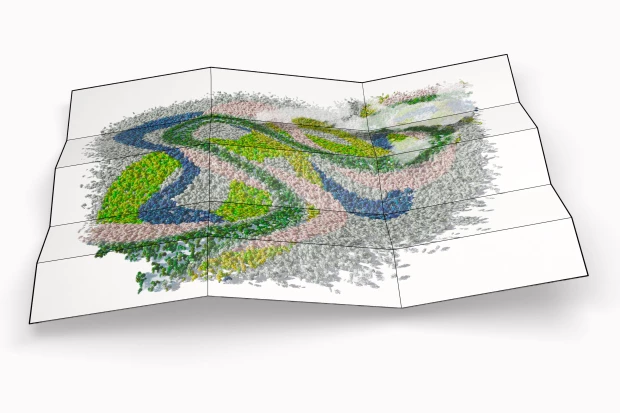

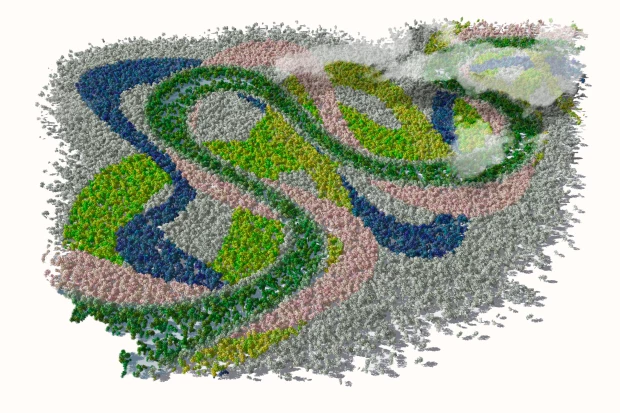

A sponge does not just hold water; it interacts with its environment. When squeezed, water gushes out; when submerged, it soaks up liquid. Aquifers can also only be understood in terms of the environment in which they are embedded. Water enters through rainfall, percolating downward, but it can also be pushed sideways by pressure or upward through springs. Movement is not linear but volumetric, expanding and contracting in response to a great variety of environmental factors and changes. An aquifer is an active participant in hydraulic dynamics.

Aquifers challenge desires for clear borders, refusing the clarity of sharp edges. If water is in constant movement, how can a clear boundary be drawn, at what scale–regional, human, microscopic? This uncertainty has political and legal consequences: if an aquifer cannot be neatly mapped, how do we regulate its use? Who owns water that flows across indeterminate boundaries, including the boundaries of property and whole nations?

Thinking with aquifers reshapes notions of water governance. The tank imaginary suggests that water is a resource waiting to be extracted, or refilled, reinforcing a logic of ownership and constant depletion. But the aquifer as sponge resists such simplification. It requires us to consider absorption rates, recharge cycles, and the constant dialogue between human and natural forces.

Legal and governmental institutions seek certainty—but the underground is a space of probability and potential. Water moves in ways that evade measurement, slipping through legal definitions. The sponge is a tool for reimagining our relationship with groundwater. By embracing its irregularity, we move away from the illusion of control that tanks represent. Instead, we confront the aquifer’s inherent dynamism —its capacity to mediate, evade, and sustain life in ways we cannot always predict. The spongey architecture is an invitation to see the subsurface not as a passive resource to be extracted and used, but as an active, dynamic architecture that depends on beyond-human beings and processes. The sponge teaches us that water is never truly contained—it is always moving, always shifting, always resisting the boundaries we impose. In a world where water scarcity fuels conflict, division and apocalyptic visions of the future world in climate change, this lesson is vital. The sponge, like our other devices of mediation of the underground, allow us to think through these urgent questions of who controls water, who protects it, and what future forums of justice will mean in a world where nothing stays still.