Michael T. Taussig, I Swear I Saw This: Drawings in Fieldwork Notebooks, Namely My Own (Chicago ; London: The University of Chicago Press, 2011).

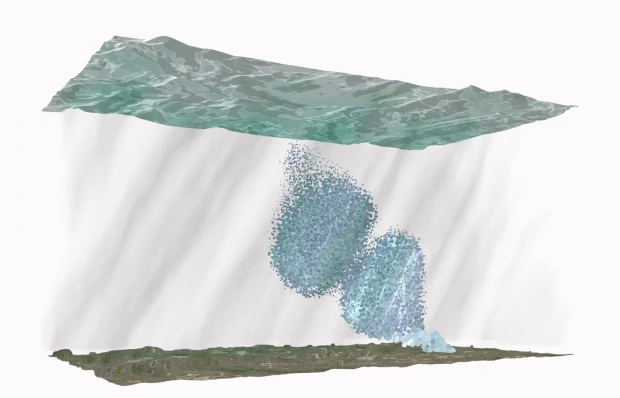

Page 3-4: “Once there was forest. They cleared the forest and grewplantains and corn. Then came the cattle. Everyone loves cattle.There is something magical about cattle. From the poorest peasantto the president of the republic, they all want cattle and they alwayswant more—more cattle, that is. The word “cattle” is the root ofcapital, as in capitalism. The communist guerrillas saw their chance.They started to tax the cattlemen, and in retaliation the cattlemenhired killers called paramilitaries to clear the land of people so as toprotect their cattle and then their cocaine- trafficking cousins andfriends and now their plantations of African palm for biofuel as well.Before long they owned a good deal more than that. They ownedthe mayors. They owned the governors of the different provinces,they owned most of Congress and most of the president’s cabinet.The just- retired president of the republic comes from Medellin, andhe too is a noted cattleman, retiring to his ranch whenever possible,to brand cows. Imagine a cow without a brand, without an owner!Running free in no- man’s- land! Once there was forest. Now thereis a nylon bag.”test avec du texte en italique

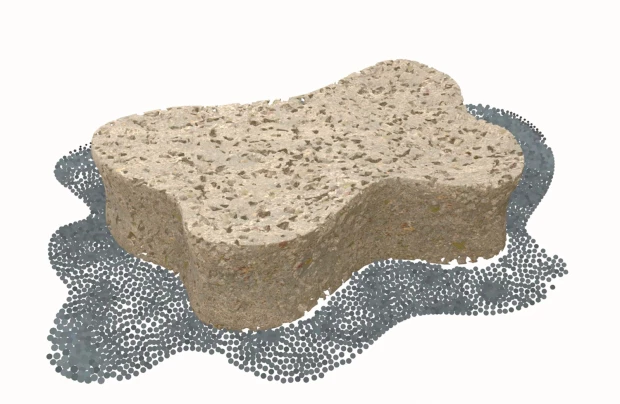

Hannah Velten, Cow, 1. publ, Animal (London: Reaktion Books, 2007).

“The term ‘cattle’ is derived from the Middle English and OldNorthern French catel, the late Latin captale and the Latin capitale,meaning ‘capital’ in the sense of chattel or chief property.”

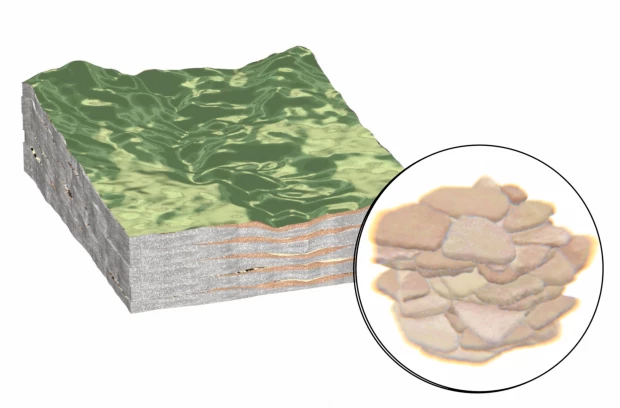

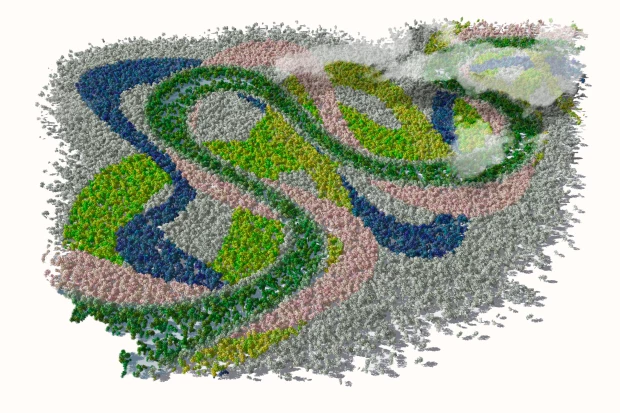

Virginia DeJohn Anderson, Creatures of Empire: How Domestic Animals Transformed Early AmericaNew York: Oxford university press, 2004. Pages 4-5: “Central to many of these narratives is an examination of the ways in which livestock helped to reconfigure New World environments to suit European purposes. By competing with local fauna, clearing away underbrush, and converting native grasses into marketable meat, imported animals assisted in the transformation of forests into farmland. These changes alone sufficed to disrupt the lives of native peoples; by contributing to erosion, altering microclimates, and introducing other ecological shifts, livestock compounded the difficulties that Indians faced after colonization began. Environmental histories thus bring Indians, colonists, and cattle together as participants in a common story, but they do so in a distinctive fashion. Because livestock tend to be discussed in terms of the ecological alterations they produced, the effects of their presence on people are largely indirect, mediated by the environment itself.”

Rosa E. Ficek, “Cattle, Capital, Colonization: Tracking Creatures of the Anthropocene In and Out of Human Projects,” Current Anthropology 60, no. S20 (August 1, 2019): S260–71, https://doi.org/10.1086/702788. They transformed agricultural fields into pastures by eating the vegetation,

Rosa E. Ficek, “Cattle, Capital, Colonization: Tracking Creatures of the Anthropocene In and Out of Human Projects,” Current Anthropology 60, no. S20 (August 1, 2019): S260–71, https://doi.org/10.1086/702788. They transformed agricultural fields into pastures by eating the vegetation,