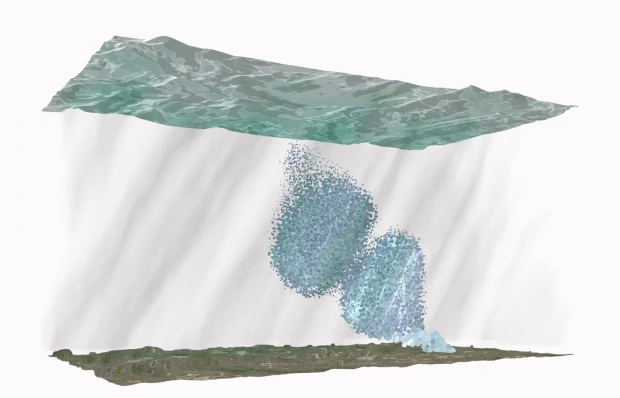

While flowing horizontally–coming down from the mountains, meandering through plains, overflowing their own banks–rivers also move vertically, taking or giving water to the aquifers beneath them. This vertical movement often goes unnoticed as it happens below the water line, that mirror-like surface which despite its seeming transparency obscures the dynamic exchange between riverine flows and groundwater movement. Rivers both gain and lose water through their interaction with aquifers. For groundwater to seep upwards into the river, the altitude of the water table must be higher than the surface of the surface of the river. And inversely, for the water to infiltrate downwards, the water table must be below the river’s surface. While the two entangled entities - the river and the aquifer - are exchanging water, they also exchange chemicals, which can affect both the ecological and biological characteristics of both the subsurface water and the river and ecosystems that it interacts with on the surface.

This intimate relationship between river and aquifer can be poignantly encapsulated in names. Take one of the aquifers in Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast. Its name is the Río Blanco Aquifer- the White River Aquifer. An aquifer that is a river that is an aquifer. If one stops to think about it, this naming convention is not surprising. Why would one presume that the river, the aquifer, and the town itself are distinct entities? Through the movement of water, people, and even pollutants, aquifer-river-town are a continuous entity constantly shaping each other geologically, geographically, and socially. But rivers have this incredible capacity to call our attention, and as a prominent feature in our landscapes, they directly impact our understanding of groundwater.

Rivers can help form aquifers and aquifers can help form rivers. For hydrogeologists, the shape of the river, its width, curvature, and the types of sediment in the riverbed all can indicate the formations of rock under the surface. For communities living near rivers, the volume and velocity of water, its ability to carry toxins and waste, all can influence the imaginary of groundwater systems. Rivers can help our understanding of interconnectivity, how water flowing from one region to another connects distant ecologies and communities. However rivers do not always clarify how an aquifer actually works. For example, the temporalities of rivers and groundwater differ in significant ways. Water resides in rivers for a relatively short amount of time - averaging about two weeks - compared to groundwater, which can reside in an aquifer for thousands of years (Freeze & Cherry 1970). Over the course of a river’s long lifetime, its movement helps to shape the underground.

The River as a Volumetric Device

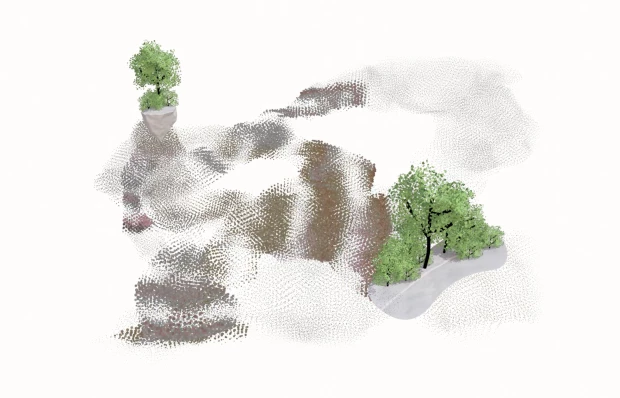

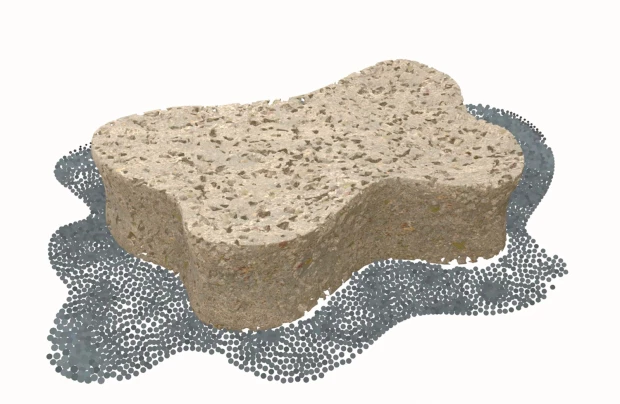

Over the Río Blanco aquifer, there is a confluence of three rivers; the Río Quito, Victoria and the Río Blanco. At this meeting point, the difference between the three rivers - the distinct waters and sediments they each carry - seem imperceptible at first glance. In the morning when we filmed the opening moments of the video shown above, where the camera dives below the surface, the waters were calm and clear, revealing the rocks and sediments that make up the river bed. The water level was low. Small fish come to bite your feet. The rocks on the riverbed hurt if you walk over them. The water level of the river rises and falls, and with this movement, the river bank expands and shrinks, the vertical movement is captured by the partially submerged rough riverbed.

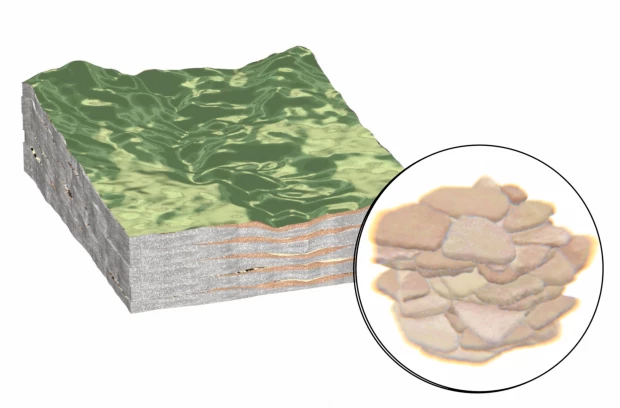

The rivers facilitate a kind of hydraulic communication between geologies as the aquifer gains its textural consistency from the sedimentary movement of these three rivers (SENARA, 2023). The geology of the Río Blanco aquifer consists of fluvial, also known as alluvial deposits, a geological formation which is developed by the physical processes of meandering rivers. It also has fractured rocks from the Uscari formation, which can be found closer to the town of Río Victoria. The Uscari formation communicates with the alluvial deposits of the rivers, evident because of the continuous saturation between the two lithologies (SENARA, 2023).

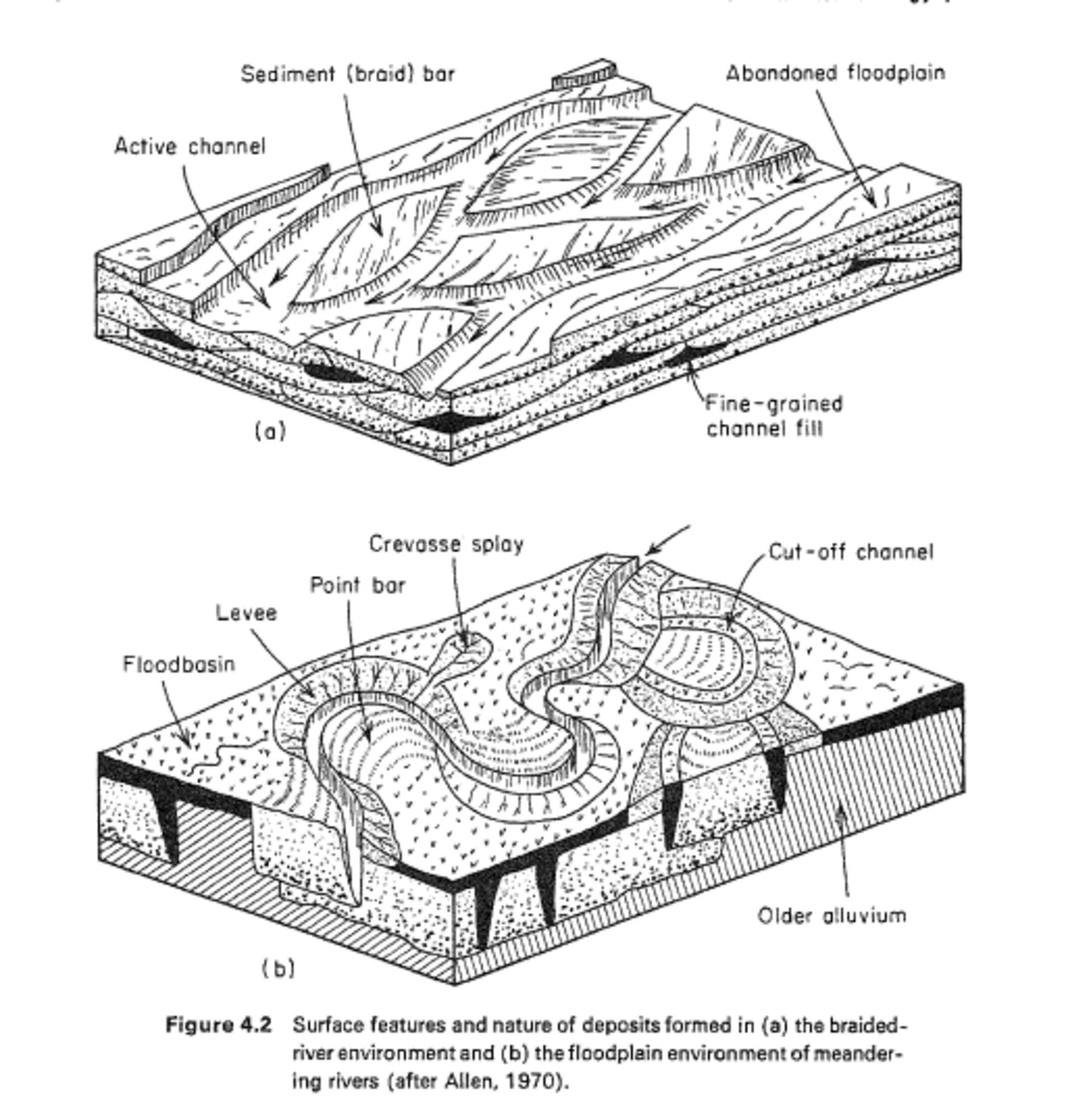

Meandering rivers complicate the act of identifying the aquifer’s edge, or boundary. Freeze and Cherry write that “because of the variability of sediment sources and flow, delineation of aquifer zones in these deposits using borehole data is a difficult task that often involves much speculation” (Freeze & Cherry, 1970: 147). This is due to the constantly shifting nature of the meandering river with “ever-changing depositional velocities” (Freeze & Cherry, 1970: 147). This change in velocity gives the underground a textural variability that defines the geological formation.

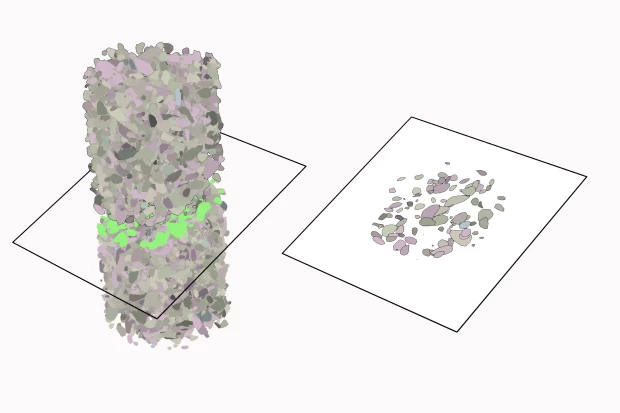

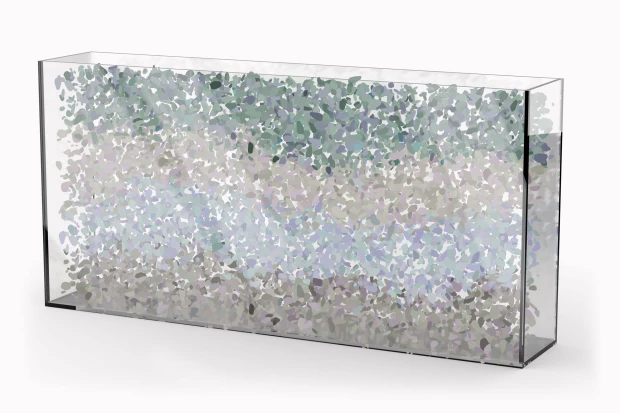

The 3D cross-sectional figures above depicting the difference between meandering and braided rivers from Freeze and Cherry (1970) challenge the 2D representation of the river, breaking with its imaginary as a series of lines separating earth from water (da Cunha, 2018). Considering the aquifer and the river together complicates this imaginary, introducing volume and depth into the river’s fundamental structure. Thinking with Ifor Duncan and Stefanos Levidis (2023), who define the river as a spectrum rather than a defined linear form, the river’s full spectrum is also composed of the geologic formations it also helps to create.

Recording of Rio Blanco, Victoria and Quito

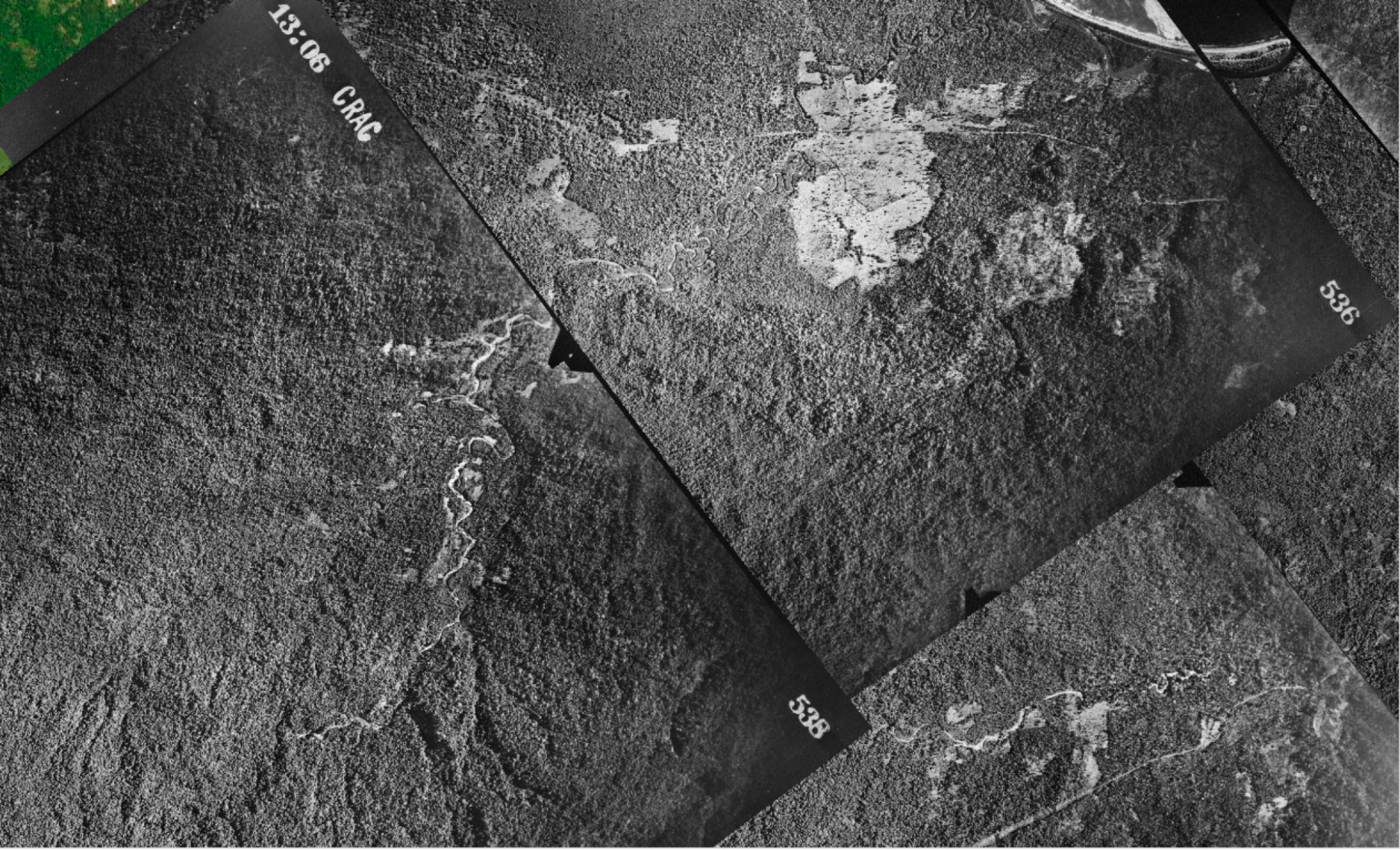

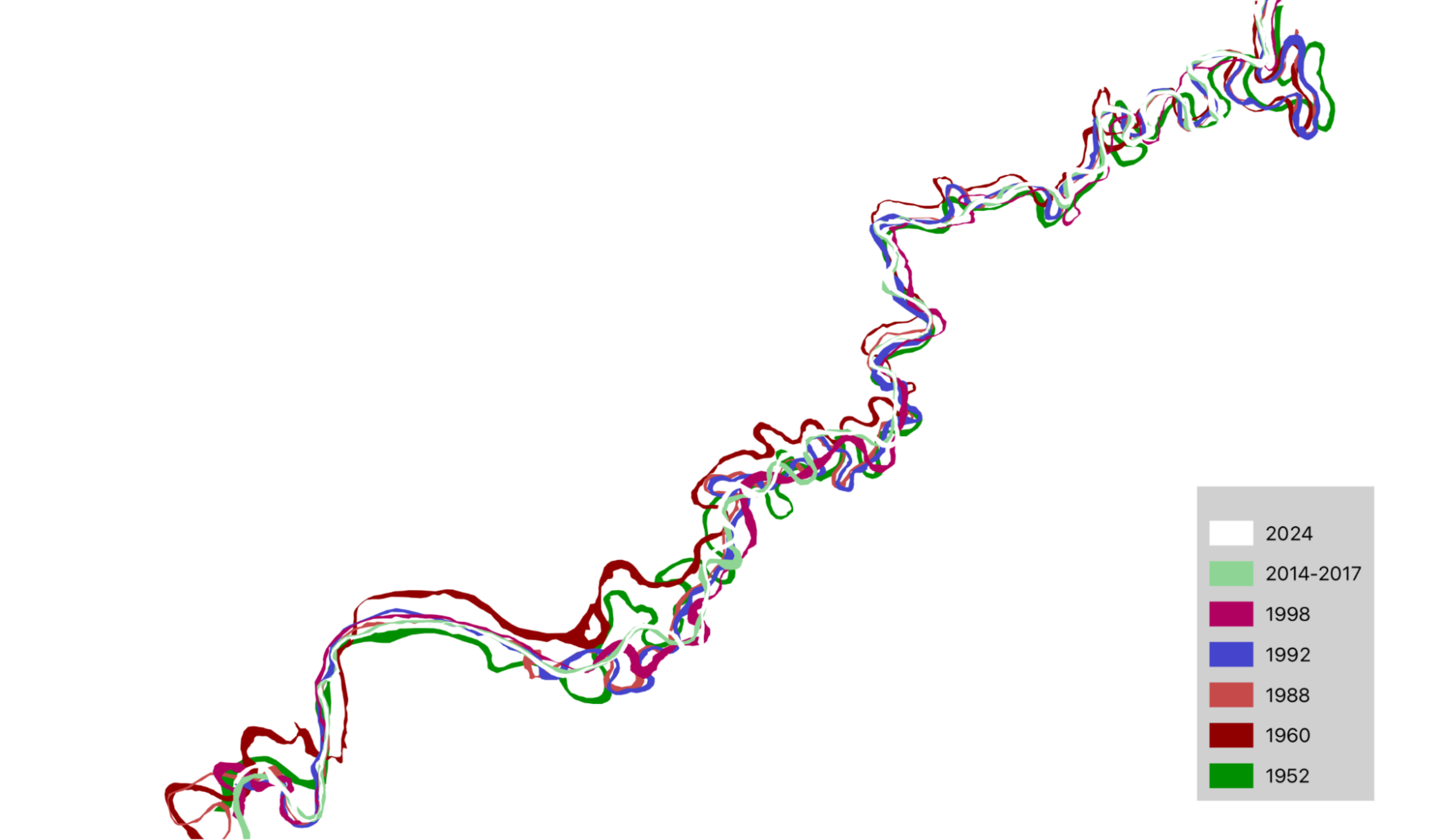

The Aerial View

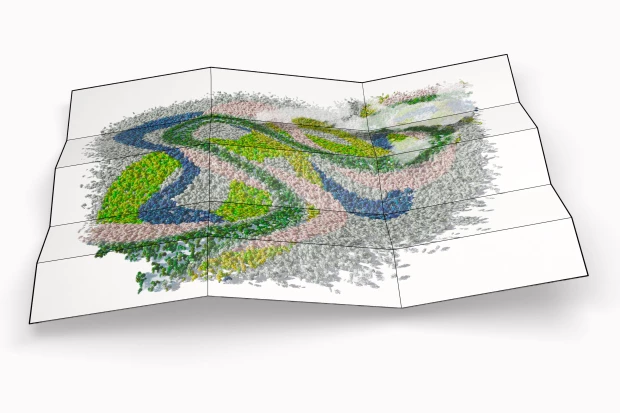

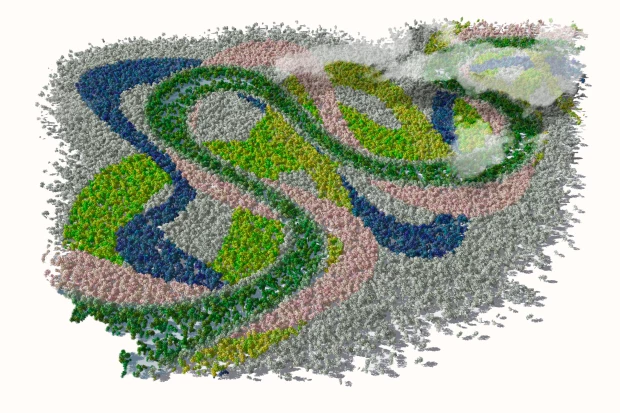

We traced the transformation of the Río Blanco, Río Victoria, and the Río Quito using historical aerial images throughout different time periods. Using these images, we can follow the river’s transformation by tracing its geomorphology over the years. From an aerial perspective, the river’s path and form changes, resulting in the river’s slow-moving undulation. This movement leaves its traces in sedimentary deposits, becoming the river’s geological footprint. When this depositing movement choreography occurs over many thousands of years, this undulation becomes embedded in the underground, forming the aquifer itself.

While we might prioritize how the river is perceived above ground, rivers reveal the tension between the underground and surface precisely because it exists between the two. Both geology, what lies beneath, and climate, what occurs on the surface, can affect the river’s form. While rivers can help to create aquifers, and are a source of recharge for aquifers, tectonic activity can also be inscribed in the river. In a place as tectonically dynamic as Costa Rica, reading a river’s transformations after a seismic event can teach us about plate movement. From the opposite end of the vertical spectrum, rain patterns play a significant role in a river’s changing curvature in tropical - or wetter - environments, such as Río Blanco. Rivers experience sedimentary movement consistently throughout the year, contributing to the transformation of its form over time.

A river can be thought of as an aquifer that resides on the surface of the earth for a period of time. It has the capacity to shape our idea of what happens below the surface, and out of human sight. In the interviews from Río Blanco, Quito, and Victoria, the river features as a prominent figure in daily life. It is a source of worry at moments, especially in regard to potential contamination flowing downstream and seeping into the aquifer. There is also the potential for flooding, in times of increased rainfall, and the worry of flooding and contamination merging and producing a serious threat to the health of the groundwater. In this region of Costa Rica there is also a concern about alluvial riverbed extraction for sand and gravel. This form of open-pit extraction involves the removal of vegetation and soil, altering the topography of the landscape. These depressions in the land can disrupt the level of the aquifer, and potentially be a risk of contamination downstreamRead more about these effects here. A WFS link to extraction concessions: https://tramites.geologia.go.cr/Geoservicios/wfs?.

The river is also a source of pleasure and enjoyment in daily life, a place to gather. The geology is also a part of this enjoyment and interaction with the river. The rock formations of the Río Victoria form slick surfaces to slide down into the water, giving a name to a particular place along the Río Victoria where people like to gather, La Resbaladera (the slide in English). In the videos we recorded of this location, the rock formations punctuate the water’s surface, interrupting and transforming its flow. These are the same rocks we can cling to or lay down on, or use them to get closer to the water’s edge.