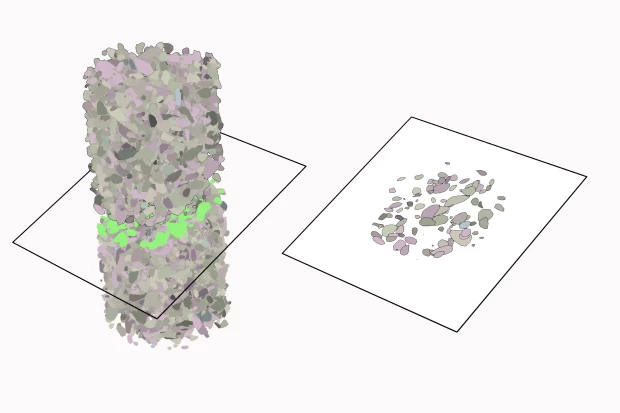

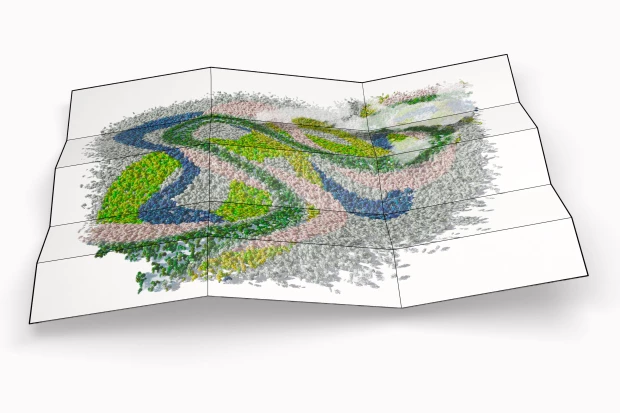

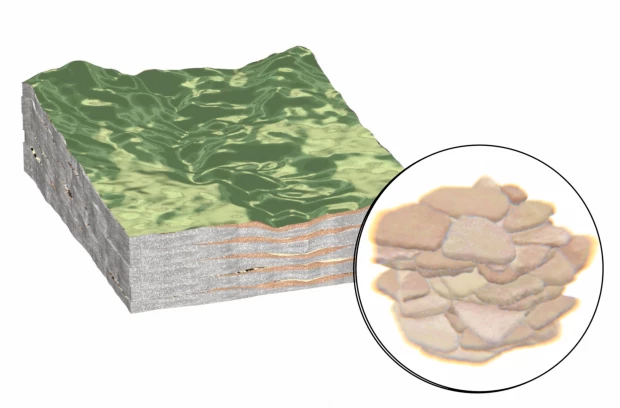

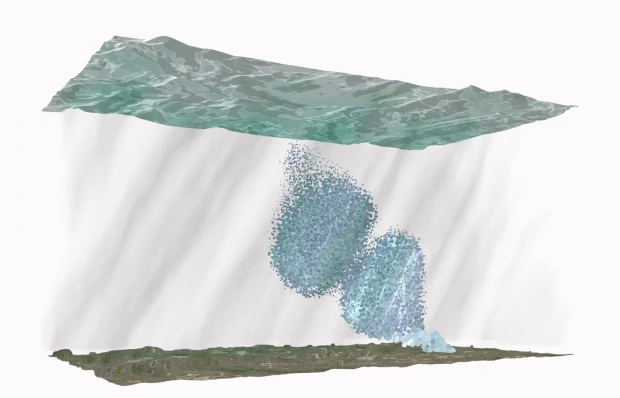

In geometry, a cross-section is a standardized method of visual representation in which an object is cut by a plane. In the field of geology, cross-sections have become the privileged mode of representing the distribution of the subsurface. Importantly, the cross section has the capacity to present the history of the earth by exposing the geological strata.

In the sixteenth century, Georgius Agricola, widely recognized as a founding figure in what would become geology, maintained constant interaction with miners to understand and sense the practical geometry that was involved in the architecture of a mine. With this experience he wrote De re Metallica – On the Nature of Metals (Minerals), which was published in 1556.

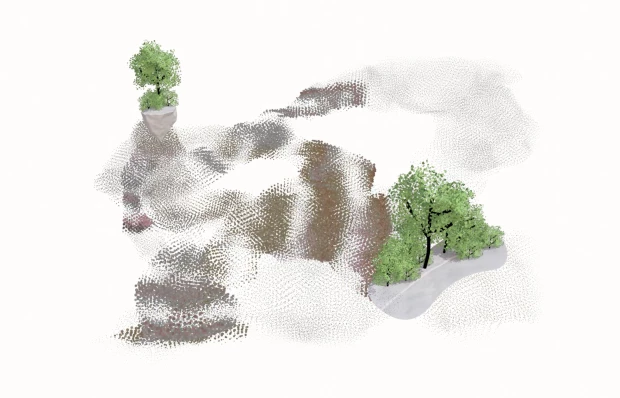

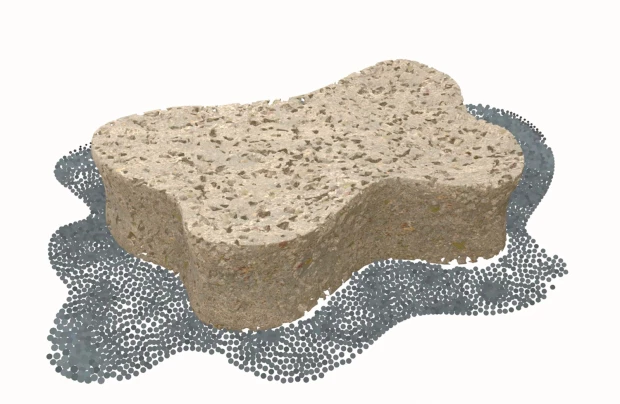

In this work, thinking geometrically about the underground meant engaging with the labor of detecting a desired metal in the subsurface, which entails differentiating a metal from other rocks and formations, and following its structure to extract it for economic purposes. According to Thomas Morel (2022) there was an empirical quality in which sensing the earth and its texture, as well as seeing geological compositions, defined the first modern-European representations of the underground and its mathematical logic. Such an objective entailed an analysis of the mountains, the discovery of ore veins and the practical geometry required to extract its content, which was then published in twelve parts. Agricola’s work was compelling to the public because it was filled with illustrations that represented multiple aspects of mining practices, mines and machines. It was also important to other scholars, because of the use of practical geometry to render the earth legible (Morel 2022: 28).

Agricola’s method of visual representation led to an obvious limitation, that seeing and sensing more broadly, were fundamental to be able to represent the underground. Further, Agricola’s work only seemed to be possible because of its connection with the needs of mining, therefore the development of underground’s geometry was inherently dependent on the practical requirements of extraction and the accessibility it permitted. What was beyond the ability of human sight was also beyond representation, and the question of how to represent geological strata did not seem to have an answer. Although Agricola masterfully used practical geometrical analysis required for mining to produce the first geometrical analysis of the underground, it was not able to significantly expand his work beyond what was seen.

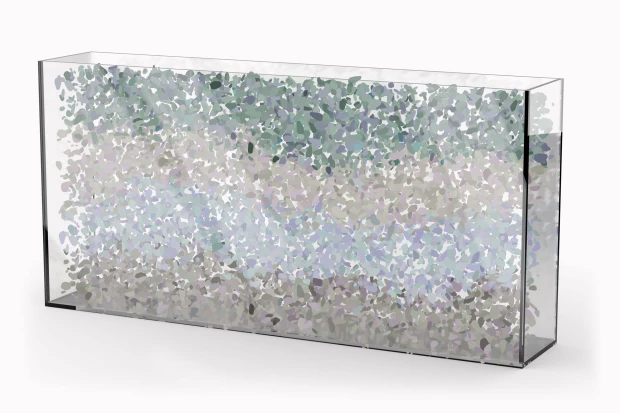

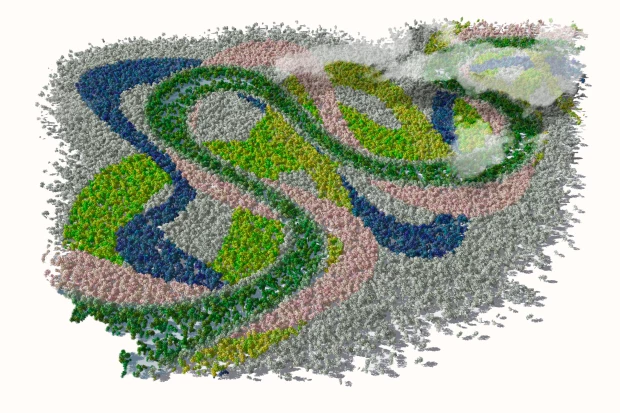

Two centuries later, drilling holes in the earth was the preferred method to access the composition of what lies beneath. Agricola’s method of sensorial access by engaging with labor was renegotiated with the access that drilling provided. The process of drilling was straightforward and still used as a method of analysis of geological layers to this day. A hole is drilled in a specific place, providing information like the layers of rocks and type of minerals, their thickness and vertical organization. However, the method of drilling also comes with another limitation, as the information from one site is insufficient to see the whole. To gain a greater insight, more holes are needed, and with this, the possibility of a comparison begins to emerge. But in the 18th century, these drillings were mostly made by actors interested in the extraction of coal, and the results were usually published in the form of a list (Fuller 1992).

Fuller explains that the cross-section was “introduced in scientific literature in the year 1719 by John Strachey” and that “Strachey assumed as self-evident that the strata were regular in their order of superposition and that they had lateral continuity through concealed areas” (Fuller 1992). The assumption of both regularity and superposition points to an idea of historicity that became increasingly important in the emergence of scientific knowledge and the political organization of the colonial world. Nigel Clark (2017) points out that the understanding of a layered earth that contained petrified artifacts of living past (i.e. human and non-human remains) informed a racialized hierarchization of the world, in which one of its representations was earth’s stratification as shown by the cross-section.