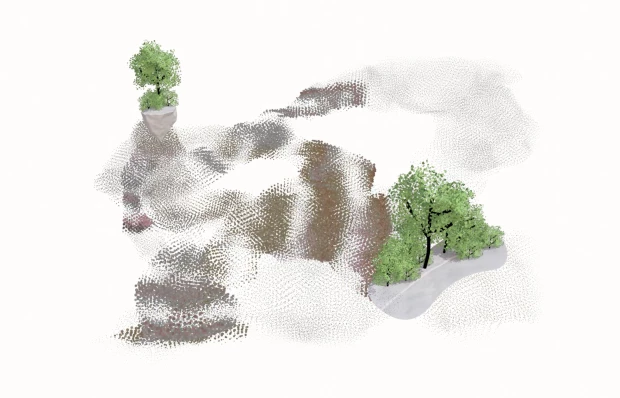

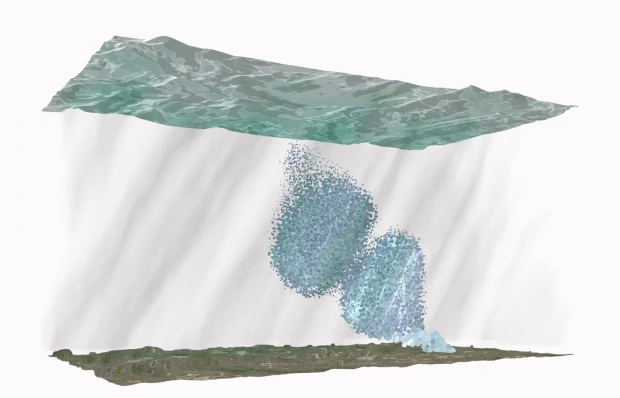

The plume is an “elemental choreography”(Ballestero, 2020) key to understanding how liquids move in the subsurface through other liquids. The plume as a form comes with a kind of warning, or associated danger to the environment and to human lives situated in the environment. Plumes conjure catastrophic events and contaminated landscapes. Plumes are of course not only underground. They can be hyper-visual, unfolding in front of our eyes. Columns of smoke billowing in the sky during a chemical fire, an oil stain floating on the surface of the ocean, gas pouring into the atmosphere from a factory. The invisible plume also scares us; the unknown form and speed of a contamination plume moving through the subsurface, below our feet and under our homes. For these reasons the representation of plumes in their various forms must be treated with care. Signs of danger inscribed in the landscape might recall events that did not exist and imaginaries of apocalyptic futures that may not come to pass.

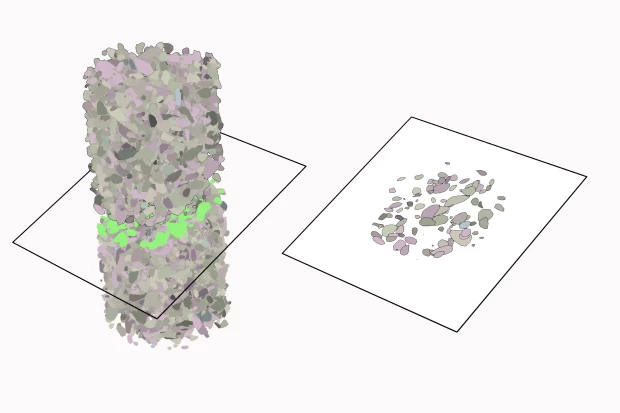

For our project, the plume is an invitation to experiment with the traditions of subsurface representation. The plume embodies the constant movement of water and substances in the underground. It emphasizes the non-static nature of the underground. Thinking through plumes moving in the subsurface also forces one to think about the materiality of this invisible space. The material nature of the underground determines the shape and form of the plume, which is to say, its movement.

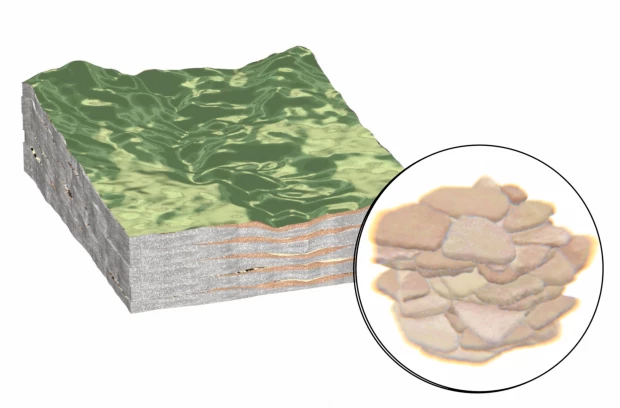

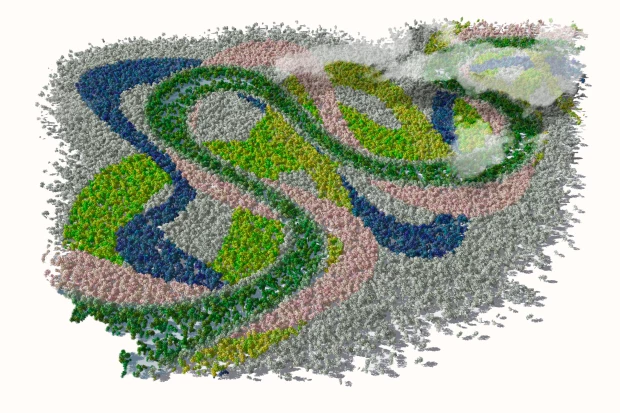

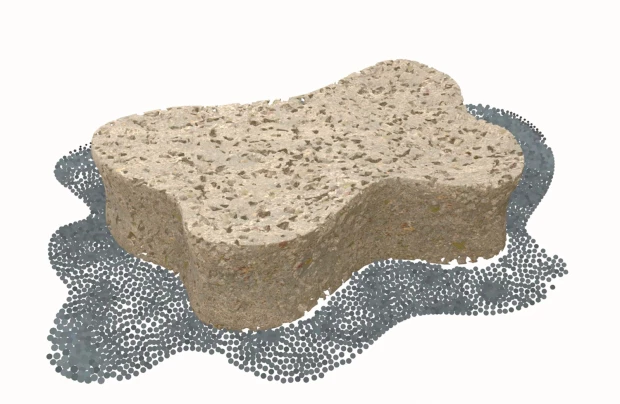

Contaminants can find their way underground in two ways: Point and nonpoint source injection. Point source occurs from a single location while a non-point source has multiple entry points. An example of nonpoint source could be an agricultural field treated with pesticides or herbicides. Contaminant transport particles travel faster on the horizontal axis versus the vertical axis. This is because of the layering of sediments and the conductivity of these different layers. Clay, which has a lower conductivity, tends to be below gravel sediments, which are higher in their conductivity. Plumes find the path of least resistance through the subsurface. Plumes move in the direction of groundwater movement, which is called a gradient - think of it as an underground very very slow-moving current. So a plume’s form - or the path it takes - is defined by two factors, the conductivity of the sediments and the gradient of the groundwater flow.

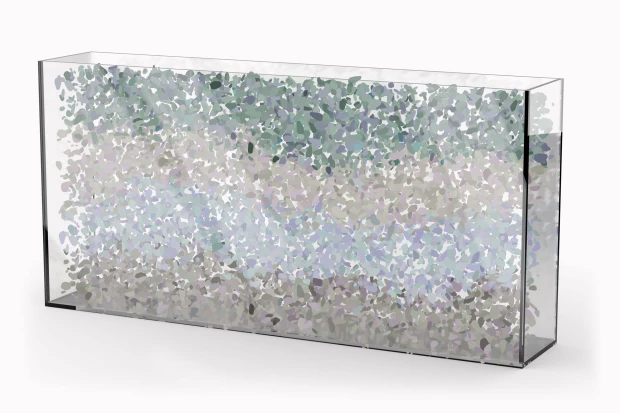

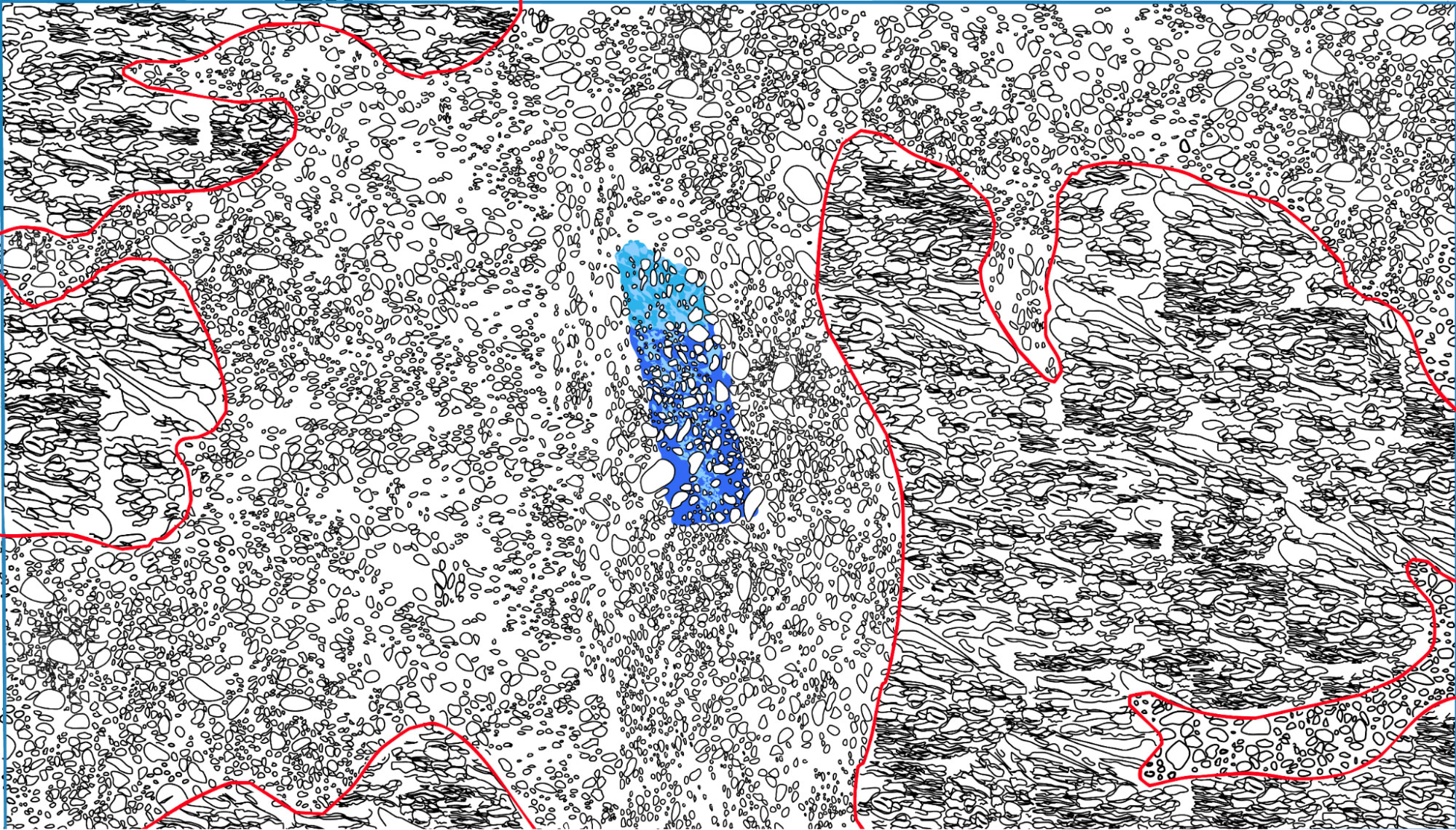

Movement and material are often difficult to represent simultaneously in traditional cartographies or cross sections of the underground. For example, the textures of the rock formations are abstracted for the cross-sectional view, often into a series of distinct and layered patterns. Movement is frozen in the 2D still image, sometimes represented with arrows, visually rendering the plume as a static condition rather than a dynamic process.

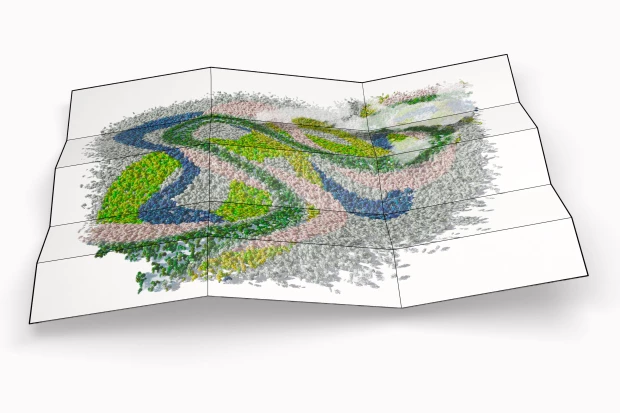

Our project experiments with drawing textures back into the subsurface in order to render movement sensible. Through visualizing texture, we might also visualize movement. Why drawing? For John Berger, whereas photographs stop time, drawings encompass time; drawings have the capability of encompassing temporalities not normally sensed by the human eye (Berger, 1972). We can draw the world in a way which exceeds human sight and scale, which is precisely what the visualizing underground demands. A way of seeing which is beyond ourselves.

Our project produced a series of drawings, both digital and by hand, which were made through a careful study of the different rock formations in Río Blanco. They are overlaid into the borders drawn by the Hydrogeological Study of Río Blanco, which include local and regional geological formations. We then took these textures and applied them to the map of two iscrones - which are a measurement of time and distance - drawn around the two wells administered by the ASADA in Río Blanco. These isocrones estimate how long a contaminant would take to reach the well from two different locations. These experiments are an invitation to the viewer to think with materiality of the underground as it relates to movement and form, and what that means for water and other liquids as they travel through the ground beneath our feet.