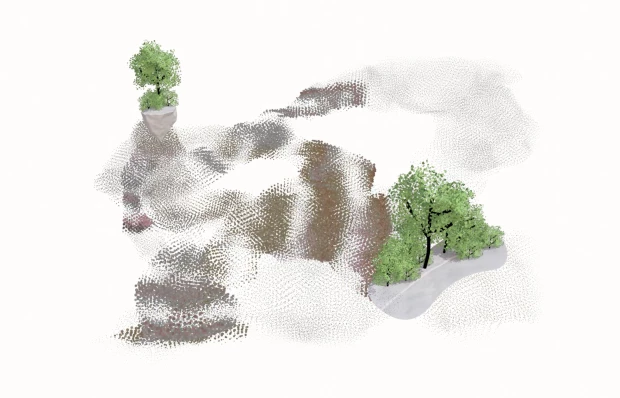

We approach rain as an action, as a process that is within a process of the hydrological cycle. In Río Blanco, it rains most days throughout the year, with a small dry season in October. In February of 2025 when we visited it rained everyday except one, thus the rain was a central figure of our daily activities, something to plan for or plan around. The rain sometimes interrupted our interviews, the deafening clatter of droplets impacting over a metal roof drowning out our voices, forcing us to stop speaking. The rain is present in many of the video recordings we made, in which you can see droplets rolling off of leaves, the surfaces of rocks are slick and glistening, the light is a delicate silver gray, from the darkened skies and the low lighting under the forest canopy. We also encountered the remnants of rain as we walked through different landscapes, finding deep mud in the fields for cattle, or puddles of water left on the ground, everything was wet to the touch.

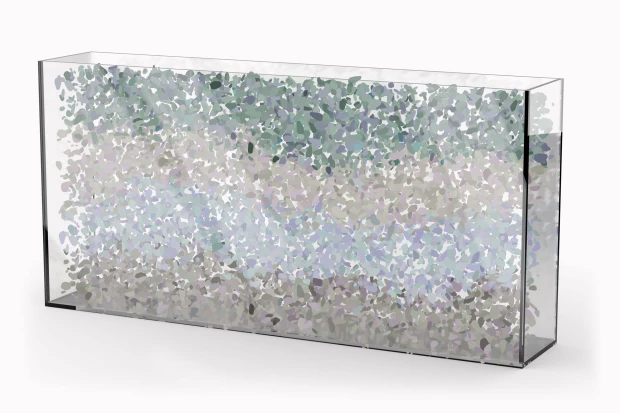

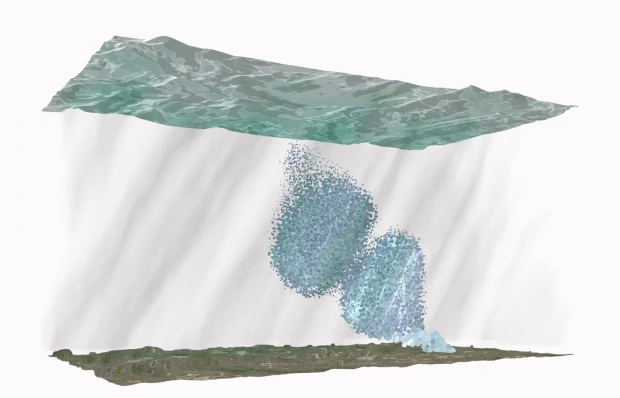

Rain is a moment in the hydrological cycle. It is the moment when H2O molecules condense and fall in liquid form. As such, because of gravity, before it hits the surface of the earth, rain emerges as the material and fluid link between its different systems. Because of its chemical mutation into different states of matter depending on the moment of the cycle, we cannot just simply follow a raindrop as it moves from the atmosphere into the biosphere and the underground. Rain is a multitude of raindrops, and it spreads unevenly through vast areas and because of the fluid transformation of H2O, once it hits the surface of the earth, it redefines lifeforms and landforms when it enters in contact with them. Hence, rain continuously reshapes the form of the earth depending on the surface that it touches: it changes the flows of rivers and riverbeds, it erodes rocks, and can reactivate or destroy entire landscapes. Depending on the specific interaction that it establishes with each surface, rain has the power to redefine its intrinsic material composition at its molecular scale, but also on a human and regional scale.

Historically in Costa Rica there was a crucial need to understand the rain, as the country moved to develop its agricultural economy (Goebel McDermott, William Anthony y Viales Hurtado, Ronny José). In “Blaming it on the Weather” the authors write that “toward the end of the nineteenth century, knowledge of the rate and intensity of rainfall acquired a particularly strategic value for the State and its inseparable associates, the transnational companies.” (Goebel McDermott, William Anthony y Viales Hurtado, Ronny José, :57). They go on to link this to the institutionalization of science in the country, whereby data concerning rainfall was essential to develop the country’s agro-export model which at that time was orientated around coffee and bananas. While rain has been the subject of nation-building discussions and research in Costa Rica, its connection to underground aquifer systems is less considered.

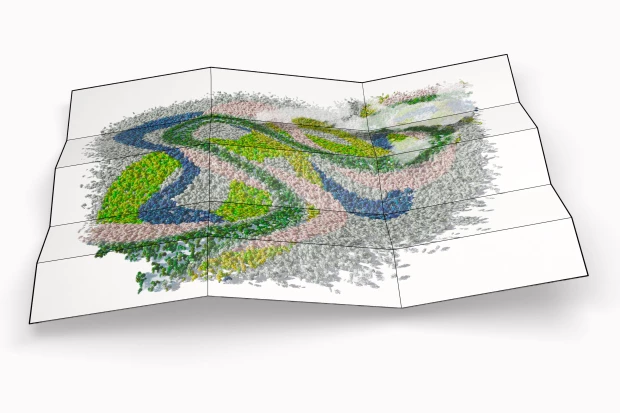

Rain is also a crucial source of recharge for the aquifer in Río Blanco, and aquifers in general. Río Blanco has a continuous relationship with the transformative characteristics of rain, especially as it interacts with the system of rivers, leading to the rise and fall of the water level, sometimes leading to floods. Rain, especially a lot of rain, in the hydrological cycle disrupts “the clarity as to the place of water” (da Cunha, 2018: 11). While flooding is often a part of the hydrological cycle, when it comes suddenly and with heightened intensity floods can become a disastrous event. Camargo and Cortesi have described flooding in this way as something that exceeds the human and defies “society by surpassing its possibilities of control” (Camargo & Cortesi, 2018: 3). They caution against solely defining floodwaters solely as a social construct because this erases “those who experience their material effects through humidity, saturation, overflow, turbulence, and submergence” (Camargo & Cortesi, 2018: 3).

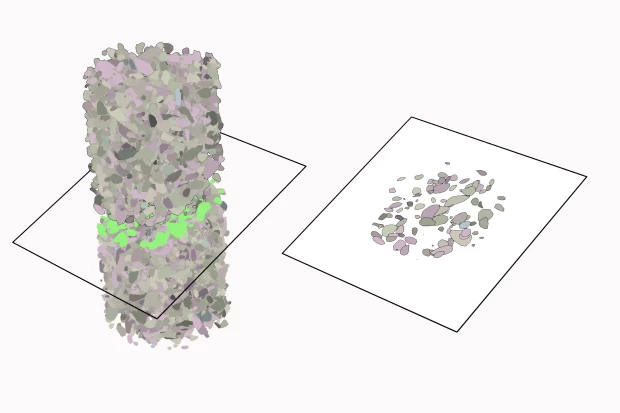

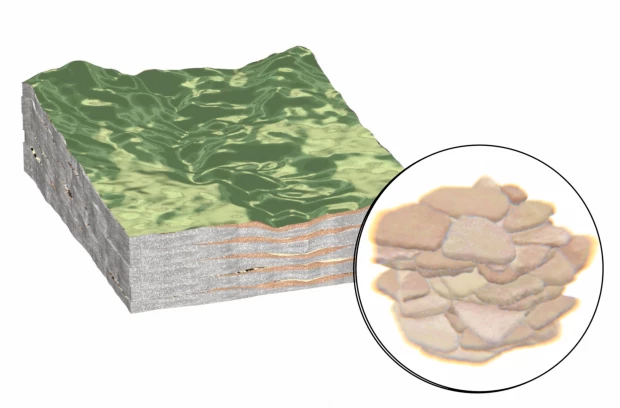

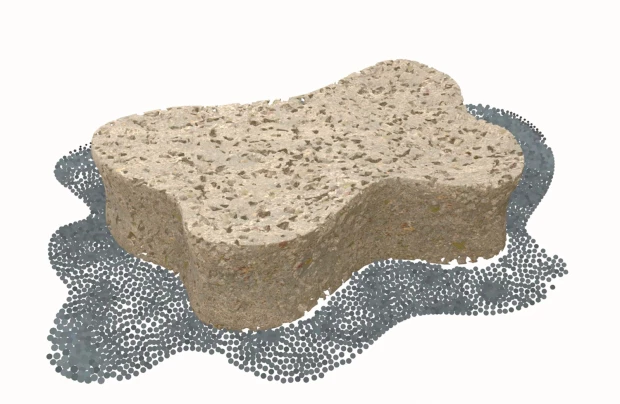

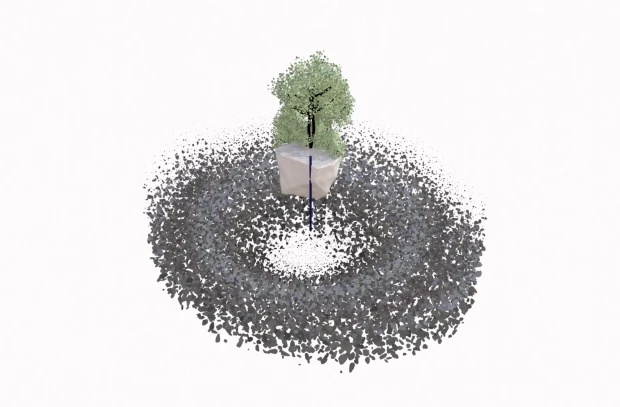

When rain descends downward from the atmosphere entering the lithosphere, the rain transfers into another temporal scale. The way in which this movement occurs differs depending on the material nature of the surface that the rain comes into contact with. The material and the material form of the landscape has at the moment of contact dictate where the water moves. Most water - around 80 percent - moves back into the atmosphere. Raindrops could fall in bodies of water (like lakes and rivers) and then flow into the underground. They could also slip into the cracks of the earth or into the molecular gaps of the soil, slowly finding their way to aquifers. Each one of these movements has different velocities that depend on the interaction between the rain and the material at hand. The ferocity of a storm could erode the soil and allow the raindrops to enter the underground with a greater velocity, but in other moments and conditions, a raindrop could take years to move through rock formations and be deposited into an aquifer.

Rain also has the capacity to shape our experience of time. The closer we are in relation to the equator, the less seasonal variation exists in terms of temperature. As a result, rain, or the absence of rain, marks seasonal shifts. The rainy season and dry season are not always consistent in their frequency and duration, and this inconsistency is becoming more pronounced with the acceleration of the climate crisis. Nevertheless, rain creates a rhythm through which life can be organized.

In Río Blanco, the rhythm of the rain is less like a pulse beat and more like a continuum, constantly present, and inescapable, hence life is arranged around the intensity of the rainfall, not its complete absence. In a workshop we conducted in Río Blanco looking back at historical aerial images of the area of rain is described in terms of intensity rather than presence or absence:

Speaker 1: [01:01:56] Es que antes cuando yo estuve aquí, las lluvias no eran tan drásticas en una lluvia que llovía, pero no, los ríos se llenaban pero no pasaban de un nivel de después desde el como dijera desde ya, desde el 2011 para acá ya se como se comenzó a notar que ha estado lloviendo más y más.

Speaker 2: [00:06:37] Antes llovía mucho acá. Entonces había muchas inundaciones. Siempre el Limón ha sido característico por las inundaciones. Siempre hay noticias de inundaciones en la época de lluvia. Entonces los ríos se ven chiquitos en el verano, pero cuando llueve es muy caudaloso. Entonces baja demasiado sedimento y, como decir se va quedando en el fondo del río, lo que hace que el cauce suba. Y se mantenga muchas veces a nivel de propiedades. Entonces cuando llueve se vienen las cabezas de agua y no la quito, pues es una comunidad que siempre ha vivido inundada.

There are areas in which the rains are more intense than they used to be, and other areas that have experienced severe droughts that did not occur in the past. These comments seem to be connected to ideas of climate change, and the idea that rain - and the weather more broadly speaking - has become increasingly difficult to manage on both local and governmental levels.

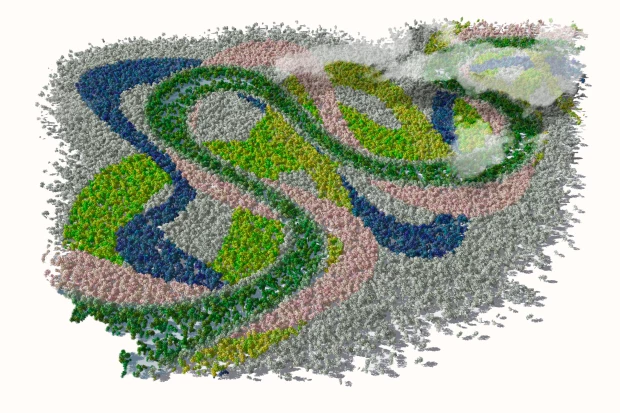

Rain is perceived as life and creation, but also as a source of destruction. Perceptions of climate change often tie rain to its destructive side, where the internal rhythm of the earth‘s cycle has been altered creating major disturbances that can be seen and felt across the landscape. What used to be a more consistent kind of rain with different intensities has transformed to specific points of violent rainfalls and arid areas. The interviews point to a tension that is directly related to the complications of managing these novel and emerging conditions of the rainfall, leading to overflowing rivers that transform their meanders because of the amount of water in them to areas that are experiencing lack of water and do not seem to be fully prepared to respond to these new conditions.

In a conversation with a remote sensing scientist, he asked us to consider the rain as something that had a temporality that exceeded our human lives: “And the water that fell is water that fell as rain 10 to 20,000 years ago.” For them, because of this other temporality, the pumping of groundwater is akin to extraction: “It’s mining in a way. Geologic fluid. It’s mining fossil water. And so all these imaginaries, even the fact that at this depth of an aquifer or of a well, the water fell to the earth as rain over 20,000 years ago.” When considering the life of the aquifer, shifting our idea of rain and the frequency of rain beyond the immediate year or season at hand is also needed if we are to understand our future in relation to the underground.