The sound of the frogs at night was louder than our voices, and I wondered how it would sound on the recording. I thought that there was a certain poetic justice to an interview about frogs being erased with the noise of the frogs themselves.

When we arrived at Fundacion Veragua the park was closed to visitors. In fact there were no people at all in the park. The sun had not set yet, and the forest was preparing itself for night. Jose, our interviewee and frog guide, was late, so we walked around the park in the dusk of the day looking for things to film and record until he arrived. Wandering around the park without any visitors gave a feeling of a moment spent out-of-time, looking at spaces where lines of people normally crowd around to look into glass terrariums with snakes, or greenhouses with butterflies, now empty and barren.

When Jose finally arrived, it was almost dark, and the chirping of the frogs grew louder. We walked to a room normally used for presentations where we sat down for the interview.

We ask him what relationship could be established between amphibians and the subterranean world? He answers:

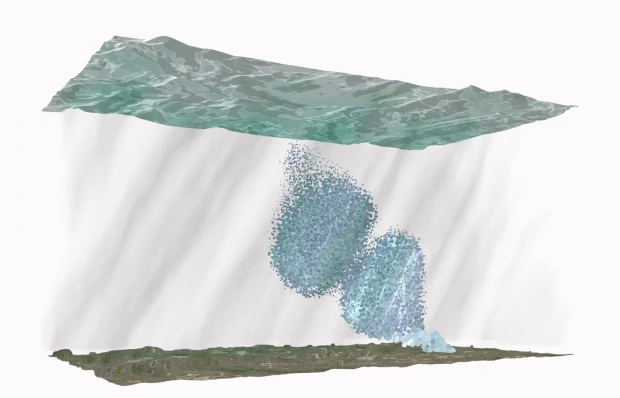

Entonces todas estas relaciones lo que hacen es como un encadenamiento. Digamos que eso acelera la productividad, digamos, de estos bosques en el sentido de mover la energía, degradan mucho más rápido la energía, aumentan la velocidad de los procesos. Todo ese aumento en la velocidad de los procesos, ayuda a que los suelos mejoren en nutrientes la escorrentía de la lluvia. Mueva todos sus nutrientes hacia las partes bajas. En ese caso puede seguir blanco así y también genera que haya una mayor fertilidad, digamos, y un mayor número de especies vegetales en los alrededores. Entonces, todos estos sistemas radicales, más la productividad de los bichos en los nutrientes de los suelos, eh? Al final van a mejorar esa filtración que hay desde la parte superior hasta la parte subterránea, digamos, en el acuífero. Entonces, si me preguntan qué relación hay, es aumentar la productividad, aumentar la velocidad de los procesos y esto ayuda a que toda esa parte vegetal sea mucho más rica y más diversa, digamos, en la zona.

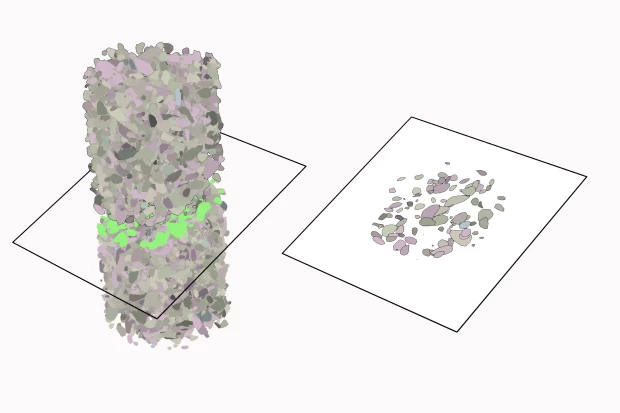

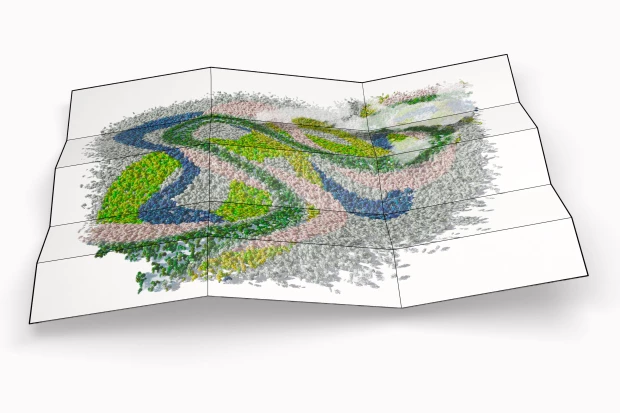

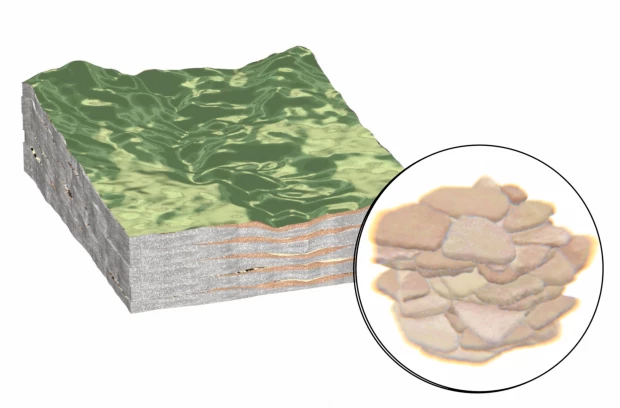

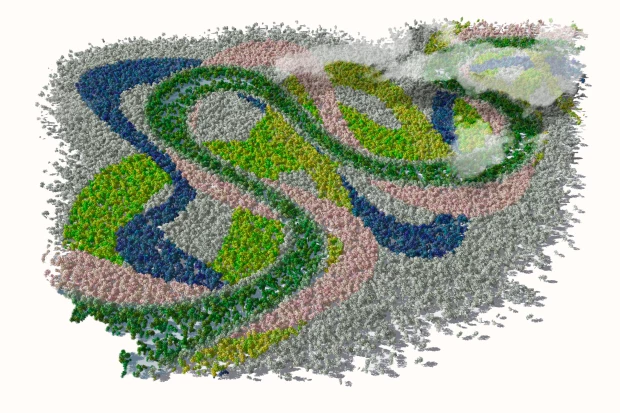

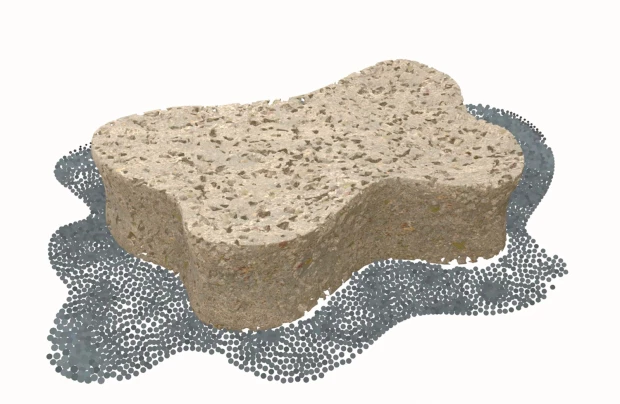

We ask why diversity is so particular to this place, where the Fundacion Veragua is situated. Jose explains that this is not only because of the diversity of the forest, but rather it is because of the diversity of types of microhabitats: the primary forest, pastureland, secondary forest, open spaces, biological corridors where different species can flourish. There are also different forms of watery bodies - both aerial and terrestrial: streams, creeks, tributaries, small ponds, rain, the humidity, all create the habitat for amphibians to thrive. So the frog, as a device of the underground, necessitates this watery landscape, which is both above and below the surface of the earth, to live.

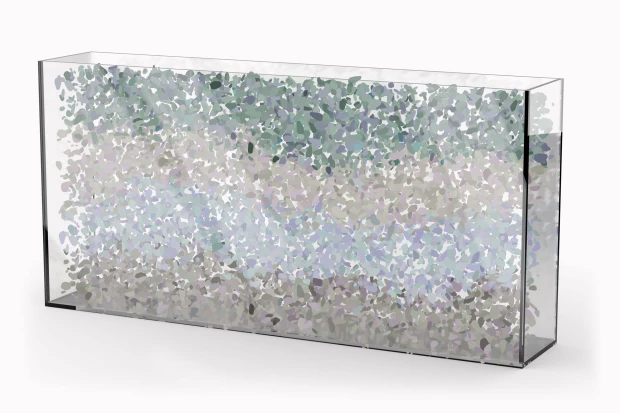

Frogs become indicator species because of how sensitive, or how permeable, their skin is to the outside world. Some amphibians breathe completely through their skin, and do not have lungs, others breathe 50 percent through lungs and 50 percent through skin. Because of how permeable their skin can be, changes in rain, toxicity or temperature can affect these species greatly. For this reason, the frog is also a sensor of global climate change.

The Rana Lemur (the Lemur leaf frog) is a critically endangered species. It’s the most endangered in the area in which we are sitting, a biological corridor which has its name because of the frog. Jose explains that here we find some of the last populations in the wild. The rana lemur used to be distributed throughout the whole country, but because of the fungal disease chytridiomycosis, which appeared in the 1980s, the populations disappeared from high altitudes. Fragmentation of land use, vegetation cover also impacted the frog population, until the last known place that the frog lives in the wild is in this biological corridor that also encompasses the aquifer of Río Blanco.

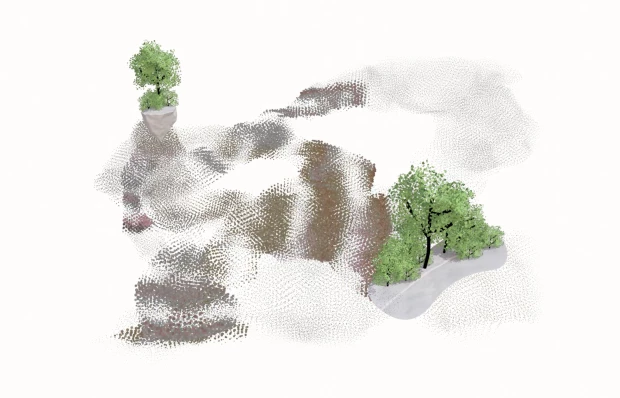

After the interview it was time to find the rana lemur. The ideal time for this was at the beginning of the nighttime hours, not too late, but also not at dusk. We walked outside following Jose who casually warned us that there was a viper who liked to hang out in the ponds at night right outside of the building we were in. Without much trouble he found the viper hanging out in the pond, right next to the path we had to walk on. We then passed the snake terrariums, where again Jose stopped and pointed out all the most poisonous snakes Costa Rica had, before saying to us, with a bit of gravitas, “Hey guys, I am not gonna lie, this is a little dangerous”. He was referring to the path down to the frog ponds we were about to take. Guiding us by all the snakes the jungle had to offer was only adding to the drama, and indeed effective, we were terrified. The path leading down to the ponds was steep, and not exactly a path, it was covered in fallen trees, brush and branches, all the things you are told to not touch if you are walking in the forest at night. Scrambling down, holding recording equipment, and trying not to touch anything, was complicated to say the least. Jose charged ahead, and soon we found ourselves around the ponds. To our surprise, it didn’t take long to find the rana lemur, Jose found one on a leaf, and picked it up gently to bring it close to record on a branch. We had to shine the flashlight on the tiny frog to be able to see her, and this we could only do for a few minutes so as to harm her with the harsh light.

We also wanted to leave. The snake terror was still in the back of our minds. We recorded the sound for a few more minutes and then left back up the terrifying path. Breathing again, it became apparent that there was a kind of performance to the whole expedition. Jose, while conveying very real conditions that were indeed dangerous, also did so in a way that was meant to impress us, while also not asking us about our direct experiences in such situations - which we both had in fact.

The foundation of Veragua caters to cruise ships that come and dock in Limon, the passengers take buses that zoom through the towns of Rio Blanco, Quito, and Victoria, and bring them directly to the foundations gates. We lost count of how many we witnessed passing through. They don’t stop to buy things, or eat, they are ferried in and out again. Hundreds of visitors, mainly from the US and Europe, come and see the conservation park, to see the snakes in their terrariums, the frogs in the ponds, and the butterflies and the trees. The money from the cruise business is a big part of how this area of conservation is funded. This is not unique to this area of Costa Rica, where the connection between tourism and conservation runs deep. But here we need to think of it as it relates to the subsurface, the aquifer, which is recharged also from the water that comes down from the mountains, where the foundation sits, is also a part of the assemblage of the frog, the tourist, and the cruise ships coming into the ports.