The emergent use of digital technologies for reversing land degradation reveals critical equity and justice concerns.

A growing number of digital technologies are increasingly aligned with an international target of restoring 350 million hectares of degraded lands by 2030. Our recently published research article in the journal Environmental Politics examines how digital platforms influence power dynamics in restoration activities. A wide range of digital devices and techniques promise a new paradigm for restoring hundreds of millions of hectares of degraded lands worldwide. Examples include digital systems for mapping degraded landscapes, robotics for tree planting, and mobile applications for plant species identification and selection for restoration. At the same time, our recent assessment discloses how digital platforms influence restoration decision-making processes that can create or exacerbate unequal power dynamics in knowledge production, funding, and market arrangements.

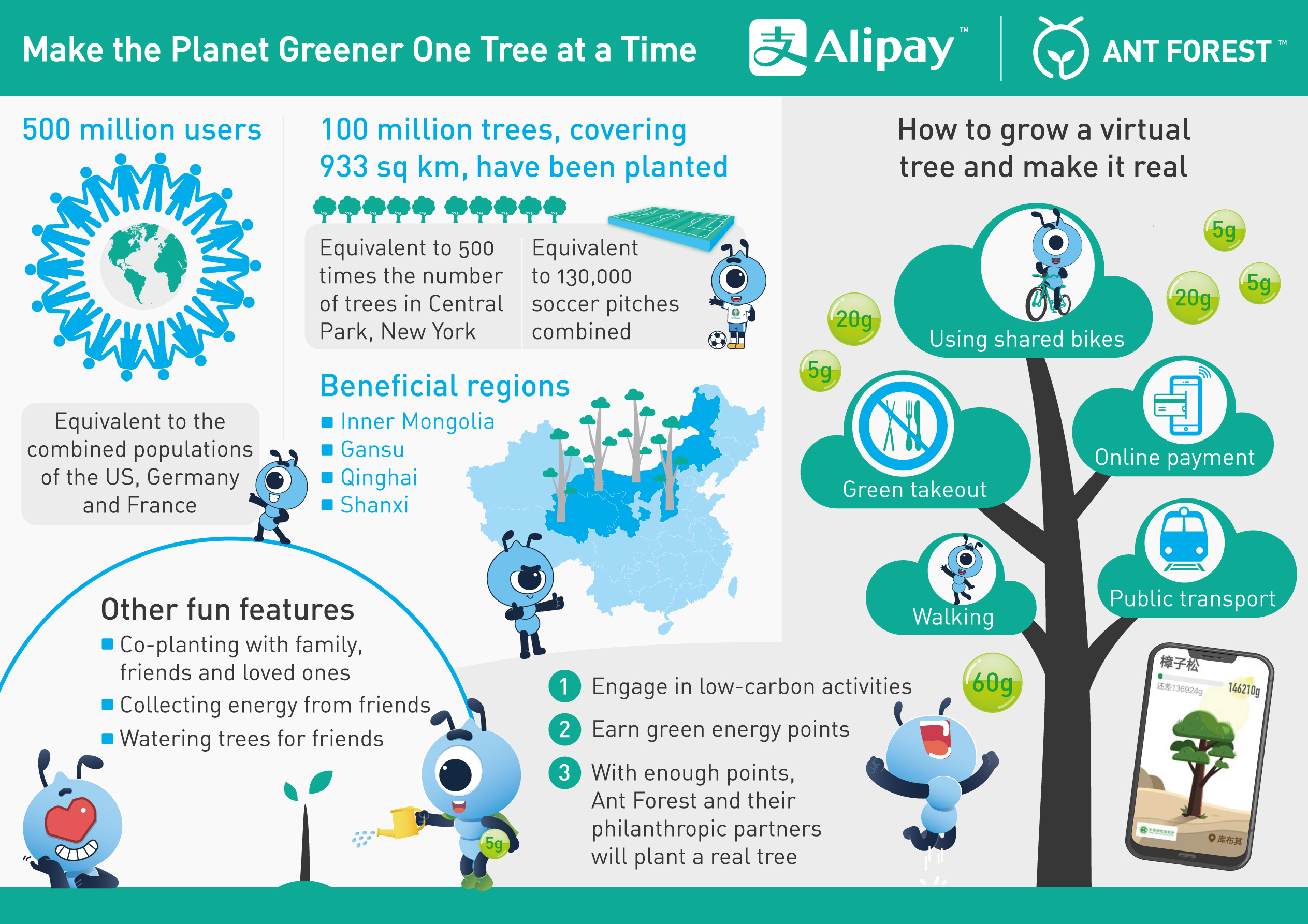

As part of a global search, we identified and tested 55 digital platforms applied to restoration activities to understand their operations. These platforms include multi-user databases, geospatial mapping and planning, smartphone applications, games, blockchain systems, crowd-funding networks, and social media. You can find the complete list of the selected digital platforms here. By analyzing these platforms, we identified four social-political drivers of technological developments. You can learn more about each of them below.

A mobile application for plant species identification. Photo: Jennifer Gabrys

Scientific knowledge to optimize forest restoration operations

This first digital development driver highlights scientific knowledge's role in maximizing tasks to implement ambitious international restoration goals and policies. Scientific expertise for restoration produces and organizes technologies to predict scenarios, select feasible methods, and create supposedly cost-effective interventions. For instance, international environmental NGOs launched the Atlas of Forest and Landscape Restoration Opportunities in 2011 to identify priority degraded lands to be restored globally. Another example is the Framework for Ecosystem Restoration Monitoring, a geospatial platform that measures the progress of restoration actions. Even though these digital platforms may help accomplish international pledges, these developments often fail to incorporate local knowledge and place-based issues to plan where and how restoration should be undertaken.

Screenshot of the Atlas of Forest Landscape Restoration Opportunities interactive map. Image source: The World Resources Institute Atlas of Forest Landscape Restoration Opportunities website. Retrieved 23 June 2022, from https://www.wri.org/applications/maps/flr-atlas/

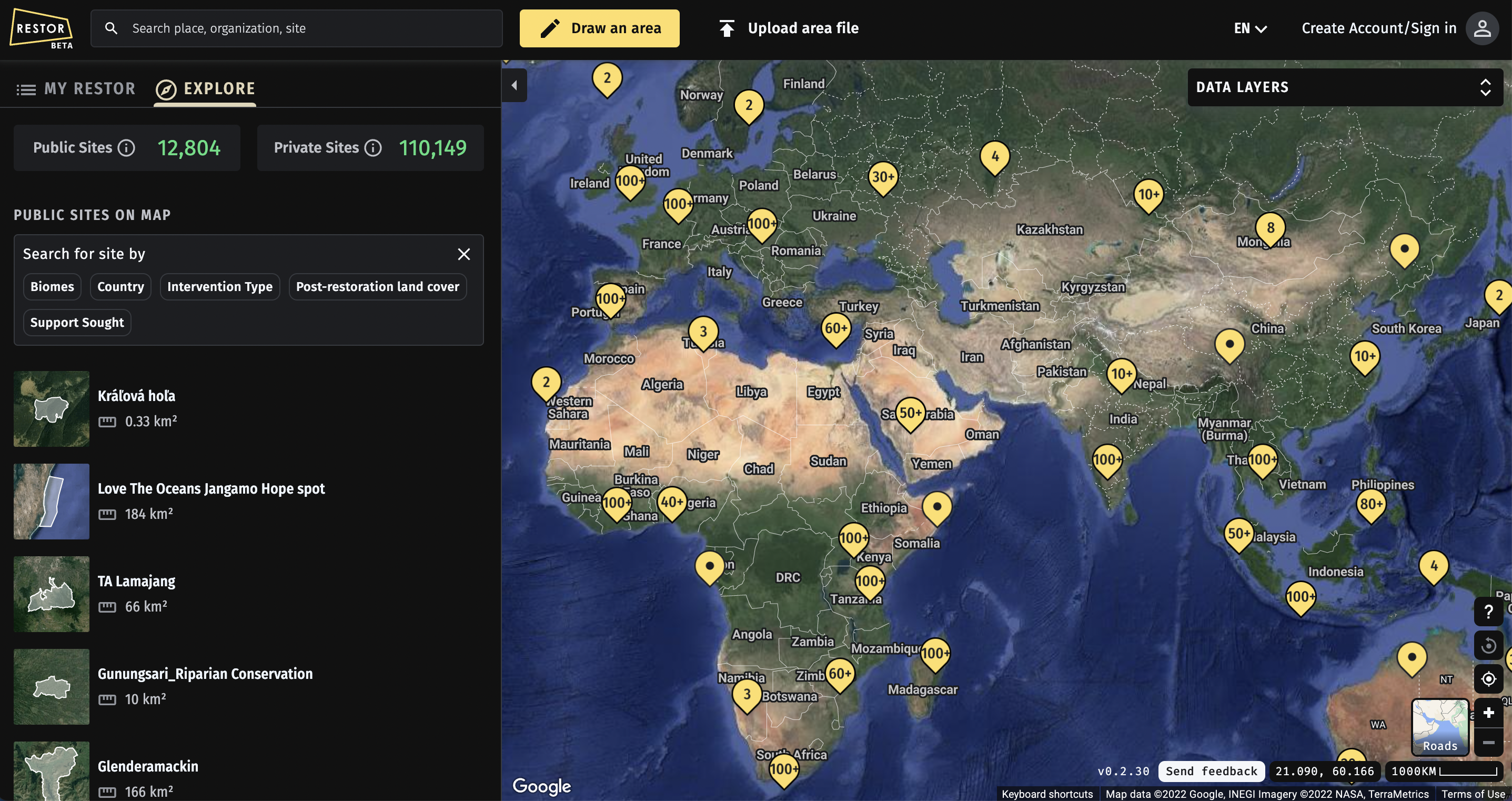

Global digital networks for capacity building

In the form of collaborative channels, these capacity-building networks interconnect diverse stakeholders for data collection, resource exchange, and communication. These digital networks seek to decentralize information, promote collaboration, and support access to financial resources for restoration projects. For instance, the Restor platform is a digital network that connects practitioners and organizations running restoration actions worldwide. The Land Accelerator program is another example of an international channel to connect multiple stakeholders in order to mobilize resources for projects at the local level. These platforms offer tools for managing systems and resources to support decision-making processes, which further generate specific models and arrangements for restoration actions. At the same time, there are several ethical and sovereignty issues on how these systems enforce particular practices and use data, particularly when these datasets are applied to develop carbon markets, for example.

Screenshot of the Restor platform. Image source: Restor website. Retrieved 23 June 2022, from https://restor.eco/

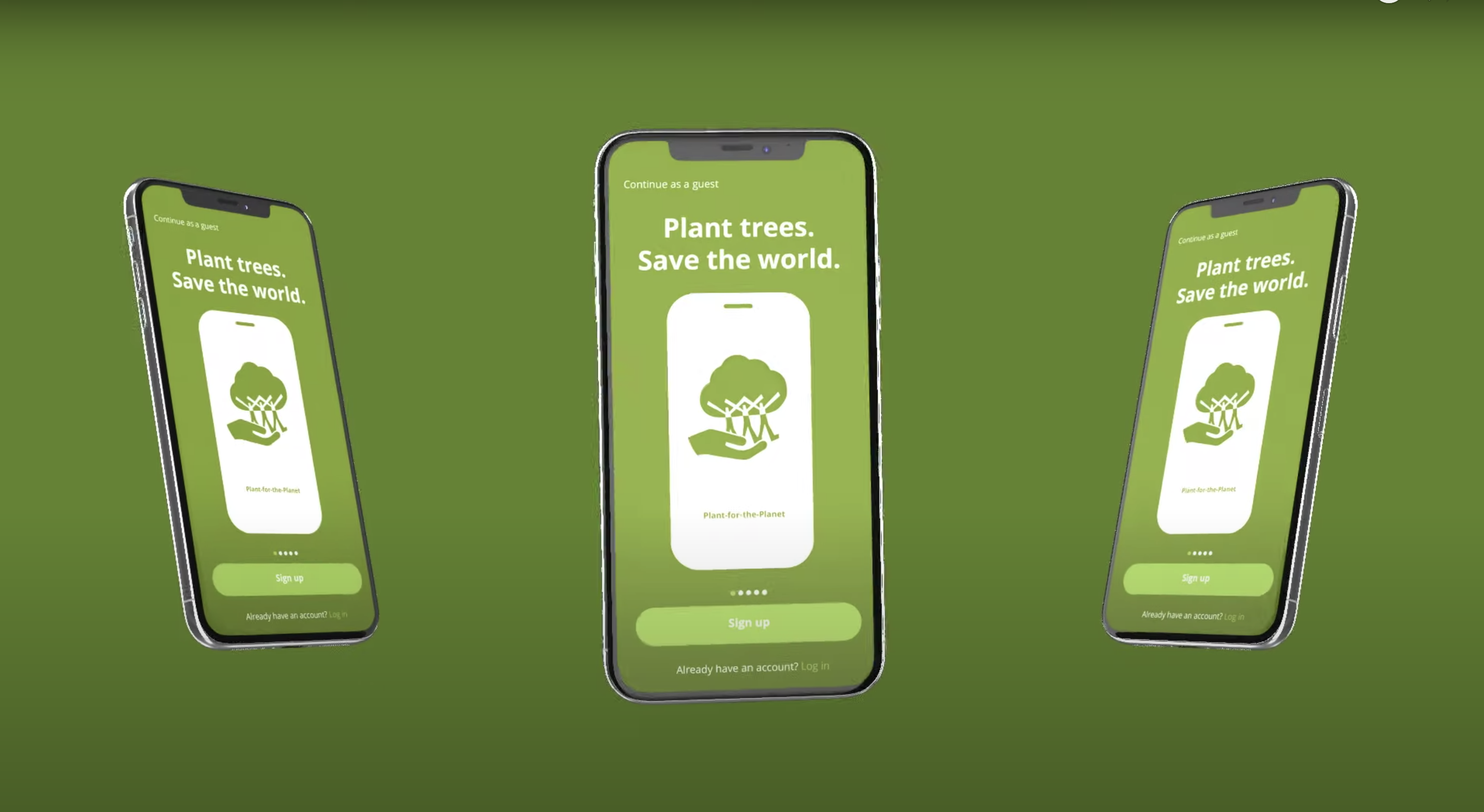

Digital tree-planting markets to operate restoration supply chains

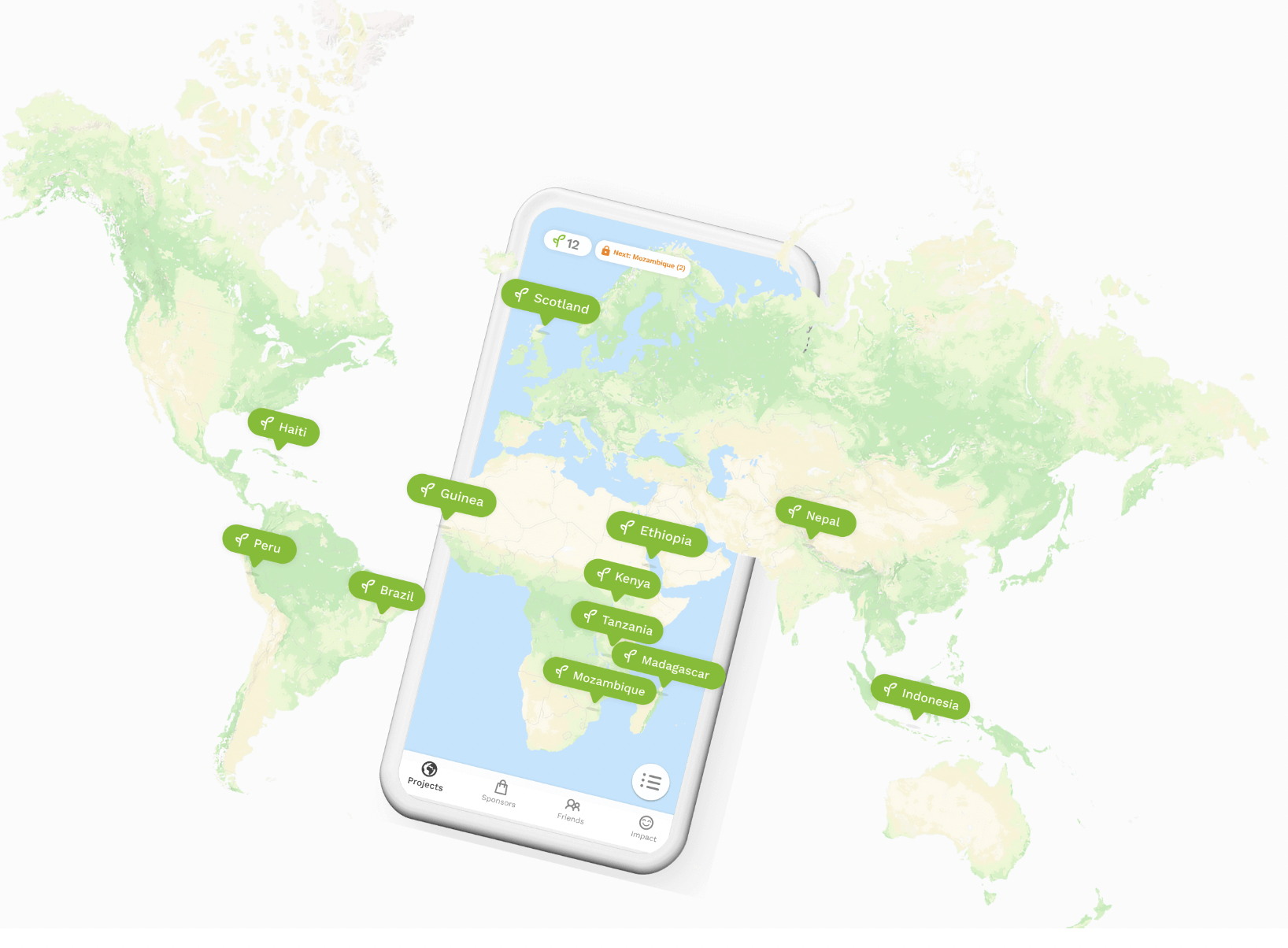

Our study also identified emerging restoration markets that are materializing through digital supply chains that link stakeholders with tree-planting commercial arrangements. Through digitally enabled networks, the British online platform, TreeApp, supports planting hundreds of thousands of trees yearly. This mobile application encourages users to engage with advertisements from several brands to generate credits for tree planting across 14 projects in the Global South. These digital restoration platforms create easy-to-use infrastructures for individuals and companies to offset carbon emissions. Still, they commonly present a potential disconnect with actual restoration practices on the ground, which could work to develop meaningful livelihood improvements and transparent restoration actions.

Screenshot of the Treeapp's website. Image source: Treeapp. Retrieved 23 June 2022, from https://www.thetreeapp.org/

Community participation in digital co-creation of restoration practices

Digital platforms are also a critical component of diverse grassroots restoration initiatives and practices of community stakeholders in everyday experiences. Community-led restoration actions adopt digital platforms to improve communication processes between local stakeholders to activate and mobilize regional restoration networks. These restoration groups and community networks are, for example, present on social media to share practices, lessons, and struggles that help share experiences and improve restoration actions. In Brazil, a partnership between community-based seed suppliers led to the formulation of Redário, a national platform to assist regional restoration networks. Redário has co-produced a seed supply management platform to coordinate commercial operations of seed suppliers with restoration markets. Notably, the co-creation process is not a simple participatory activity and may not always include the diversity of local values, interests, and financial goals.

These four different drivers of technological developments highlight how digital platforms can shape restoration projects. This study suggests the need for critical attention to these emerging environmental technologies to comprehend how knowledge and expertise are coded into the politics of platforms. Such platform-led restoration actions can contribute to and amplify inequality issues when implementing restoration initiatives across scales.

For more information, you can access the full open-access article at:

Urzedo, Danilo, Westerlaken, Michelle, and Gabrys, Jennifer. "Digitalizing Forest Landscape Restoration: A Social and Political Analysis of Emerging Technological Practices." Environmental Politics. DOI: 10.1080/09644016.2022.2091417.