"Through the reacquisition of forestlands, the [Yurok] Tribe is engaging in forestry practices guided by traditional knowledge and contemporary scientific knowledge with the goal of restoring the forestlands to a dynamic ecosystem the forest once knew and allowing Yurok Tribal members to interact with the landscape as they have done since time immemorial."

Frankie Myers (Vice Chairman, Yurok Tribe), Testimony Regarding Natural Solutions to Cutting Pollution and Building Resilience, US Congress, October 2019

Screengrab from the Perhutana promotional video, showing a forest certificate for investing in the forest. Image source: Jatwiangi Art Factory [screengrab]. Retrieved 13 July 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vScXg4BUur8

Indigenous peoples, local communities, and social and environmental organisations are combining forest knowledges developed over generations with emerging digital modes of communication, mapping, and monitoring in order to build capacity for self-determination in forest governance and relation in the context of ongoing colonialisms and environmental change. The examples in this story sustain and adapt longstanding forest practices and socio-ecological relations variously through digital platforms, GIS mapping, aerial imaging, and NFTs. They mobilise these technologies towards land, data, and epistemic sovereignty against persistent and renewed forms of dispossession and environmental injustice. These projects reveal the complex, often contradictory processes of navigating uneven state, neoliberal, and Indigenous modes of environmental governance in Indigenous and community efforts to reclaim and restore more-than-human forest environments.

Cosmopolitical forests

In a forthcoming article, Smart Forests researchers propose a cosmopolitical approach to forests that attends to the multiplicity of beings, stories, and socio-technical practices that constitute ways of knowing and inhabiting forests as pluralistic assemblages. The article builds on scholarship that presents forests as political entities constituted through territorial governance strategies and technologies of measurement, classification, and calculation. As Indigenous scholars and activists have argued, such modes of datafication have often been operationalised for the material and epistemic containment and extraction of Indigenous lands, bodies, and knowledges (Tuhiwai Smith, 1999). In this context, the Indigenous projects discussed in this story highlight different modes through which technologies materialise multiple, uneven and frictional forest worlds.

Practitioners prepare the mix of seeds for land restoration through direct seeding through the Xingu Seed Network. Image source: Tui Anandi [photograph]. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

Forests as networks / infrastructures of restoration

The Xingu Seed Network started as a grassroots initiative led by Indigenous communities and local farmers in southeast Amazonia/north Brazil for collecting and supplying native seeds for landscape restoration. The network involves over 500 seed collectors, many of them women, and promotes knowledge sharing around seed collection practices and technologies. In a region undergoing high rates of deforestation, seed production offers alternative forms of income generation to agricultural expansion, logging, and mining. There are now multiple seed networks in Brazil, and the digital platform Redário facilitates communication and coordination between them.

In the forests of the Klamath River Basin in California, the Yurok Tribe has used different strategies to support environmental restoration and Indigenous sovereignty. In 2013, the Yurok Tribe negotiated participation in the State of California’s cap-and-trade carbon offsetting scheme, and with the income from carbon credits bought over 60,000 acres of previously dispossessed ancestral lands from a timber company. They also developed an Environmental Program that implements Yurok forest management approaches (including controlled burns) and habitat restoration in the Klamath River watershed. The carbon financing of this work has raised some debate among tribal members concerning complicity with polluting and extractive industries, but the Yurok Tribe’s approach has offered a model for reclaiming land that has since been taken up by multiple Native nations across North America. The Yurok Tribe has recently been supported by a $5 million grant from the US Department of Commerce to support the use of high-resolution environmental mapping, LiDAR, and aerial imaging technologies in their environmental restoration programme.

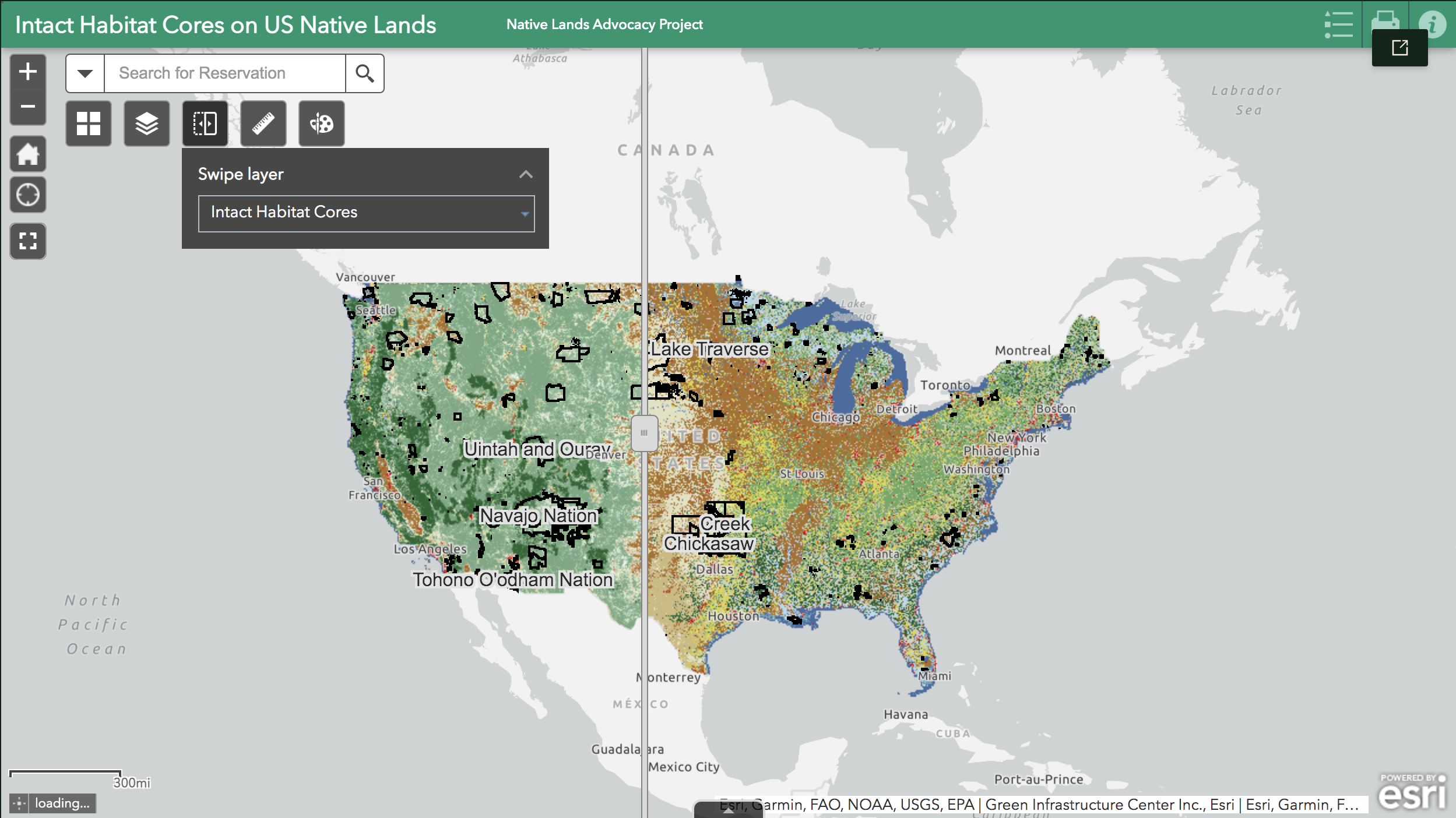

Screenshot of the Preserving Intact Habitat on US Native Lands map. Image source: Native Lands Advocacy Project [screenshot. Retrieved 13 July 2022, from https://nativeland.info/blog/storymaps/preserving-intact-habitat-on-us-native-lands/

Environmental mapping, monitoring, and data sovereignty

Indigenous communities are using monitoring tools to map the impacts of resource extraction, land grabs, environmental degradation and climate change in forest environments. In the Amazon, platforms such as the System for Observation and Monitoring of the Indigenous Amazon (SOMAI) and the Amazonian Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information (RAISG) gather environmental data on deforestation, land use, infrastructure, and socio-environmental threats such as fire and drought, providing information and political tools to support Indigenous organisations and demands. In the place currently known as the United States, the Native Land Information System (NLIS) offers mapping and data tools for Tribes and Native communities, with the aim of supporting habitat protection and restoration through Indigenous frameworks of relation to land. A central element of NLIS’s work is building Indigenous data sovereignty, emphasising governance over the collection, ownership, and use of data. For example, a recent storymap proposes generating data on Native lands in term of "Intact Habitat Cores" rather than the more well-known framework of Key Biodiversity Areas, because Indigenous peoples have often not been part of consultation processes around KBAs.

Screengrab from the Perhutana promotional video, showing a soil brick certificate for investing in the forest. Image source: Jatwiangi Art Factory [screengrab]. Retrieved 13 July 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vScXg4BUur8

Mobilising community through Indigenous media, arts and social practice

Finally, Indigenous and traditional communities are utilising a range of media to communicate and build networks around Indigenous environmental knowledges, cultures, and political struggles. Examples include community-led podcasts in Brazil, such as Copiô, Parente!, which communicates how federal political decisions impact Indigenous territories, and Povos e Comunidades Tradicionais do Brasil (Brazil’s Traditional Peoples and Communities), which shares local leaders’ thoughts and oral histories around land struggles and community mobilisations.

In West Java, Indonesia, Perhutana is a social forestry project that plans to reclaim 8 hectares of land in the Majalengka district as conservation forest for the people living there. The project operates on the basis of investment into forest plots, using NFTs to certify ownership of plots to be later donated to the community forest. Perhutana was launched by the arts collective Jatiwangi art Factory at the international art festival documenta Fifteen, which took place in Germany in 2022, and was also shared online. Moving across political and aesthetic terrains, multiple knowledges and technologies, Perhutana attempts to address ongoing dispossession and environmental change through engaging with but also exceeding neoliberal state frameworks of understanding and calculating forest value.

For more on cosmopolitical forests, look out for the forthcoming article:

Gabrys, Jennifer, Michelle Westerlaken, Danilo Urzedo, Max Ritts, and Trishant Simlai. (2022). "Reworking the Political in Digital Forests: The Cosmopolitics of Socio-Technical Worlds." Progress in Environmental Geography, 1(1–4). https://doi.org/10.1177/275396872211178.