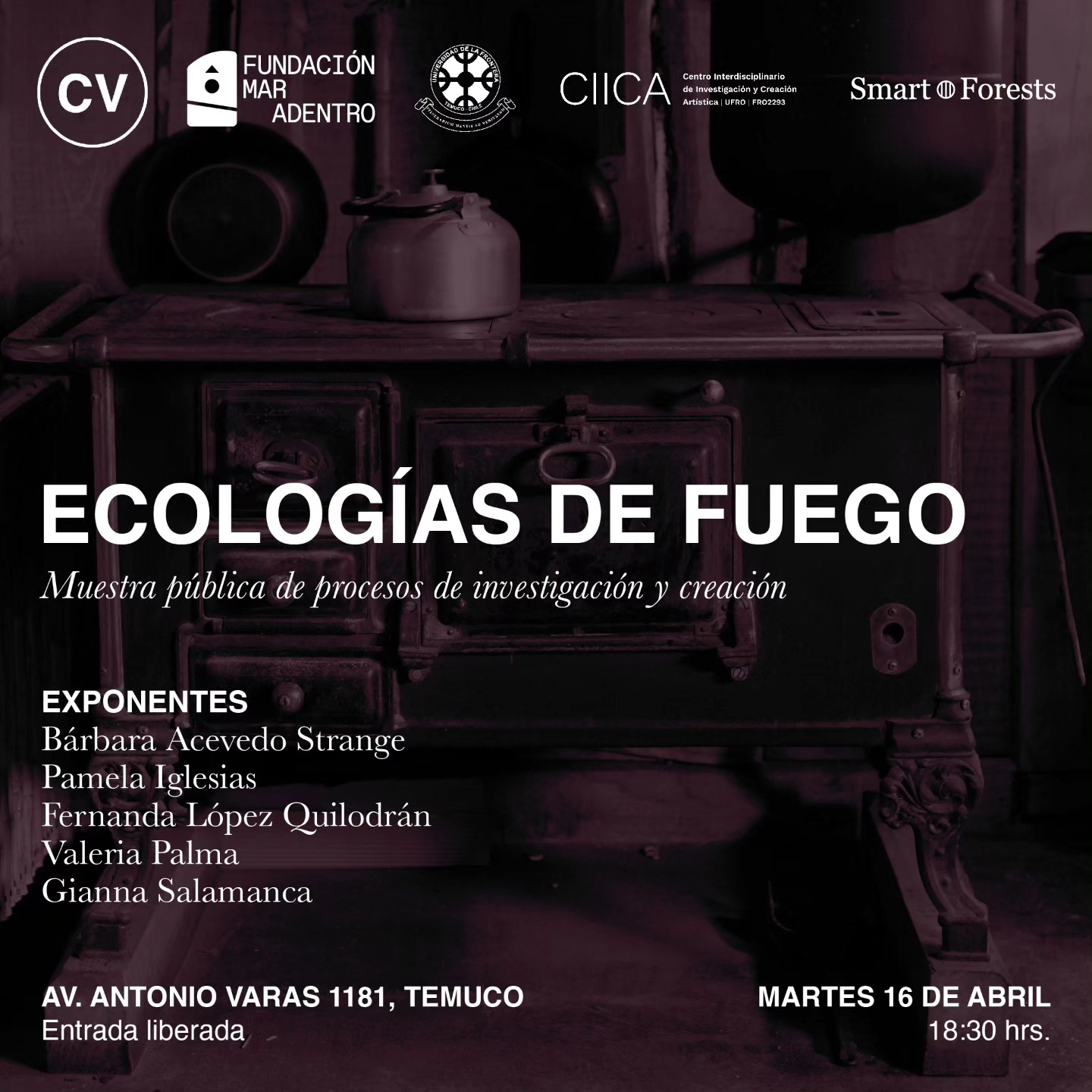

At the Field School in Bosque Pehuén, we met with part of the FMA team and the five residents of the "Ecologies of Fire" program, artists and researchers Bárbara Acevedo, Pamela Iglesias, Fernanda López Quilodrán, Valeria Palma and Gianna Salamanca, who approached fire from apocalyptic, biocultural, ecofeminist and scientific narratives, focusing on the interactions of this element located in the temperate rainforests of the south. Through an exchange of knowledge, experiences, field activities, study of archives and images, they conducted collective explorations on the epistemologies of fire, its interrelations with climate change, and meanings according to diverse worldviews present. The results of their research were presented in a public program on Tuesday, April 16, 2024 at Casa Varas, Temuco.

Ecologies of Fire public exhibition at Casa Varas.

During our visit to Bosque Pehuén, the idea was to have an opportunity to share stories and perspectives on fire and fires with those who have participated in collective research, practices and debates. They have been reading the signs of fire, both in the physical and cultural landscape. Therefore, getting together to talk around the fire (the one in the fireplace) and then going for a walk in the Andean forest, were our means of approaching these experiences. All this, as a way of working towards a pluralism of fire ecologies, to broaden our understanding of fire as a set of social, environmental and technological interactions and systems.

Walk through the forest of Bosque Pehuén.

Stories about fire and fires

For the next few hours, we talked about our experiences and studies of fire and fire in response to specific questions: What are the material, visual, sonic or other sensory components of fire in our work? What are the different narrative components of fire? How does it circulate through space-time, memory and experience? After a short break, we walked through the forest to a place where we could observe and discuss fire signs in the landscape, with an emphasis on understanding what we mean by a fire sign and what its history is.

In order for us to understand the different stories we tell about fire, it was first necessary for us to understand and visualize from which places or by whom these stories are told. Currently in Chile, due to its social, political and natural context, we have been strongly affected by fires and influenced by an insufficient action to address the emergency of this socio-natural problem, a vision of fire and fires as a public enemy, which threatens our welfare as inhabitants of such diverse territories, has been widely disseminated. Little do we reflect on fire as an essential element for life, which shapes natural and social relations. This vision of fire as something to be feared has not allowed us to see other aspects that are fundamental to understanding the relationship of ecosystems and human beings with fire. We have focused the social debate only on aspects such as: attack, combat, control, domination. We have reproduced reified ways of relating to fire and, as part of its elements, to nature itself. For this reason, as it happened to us that day, we found it necessary to talk about fire as something that drives away and as something that brings us together.

Araucaria tree line in Bosque Pehuén.

When we tell the story of fire only from a satellite view, from a territorial planning or physical landscape scale, it is easier for us to review territories prone to risks associated with fire, but that fire understood from a highly anthropocentric notion. On the other hand, when we challenge ourselves to approach an experiential or immersive scale and delve into the socioecological relationships of the cultural landscape, we see other stories about fire and we see its connections, longer and more complex than we thought. We even see how some species that have been considered pests appear after forest fires, but may have a key ecological role for the bioavailability of certain nutrients in the forest floor.

According to one of the residents, one of the tree species related to the pests is quila (Chusquea quila), a type of bamboo endemic to the forests of southern Chile. This species plays an important role in the undergrowth, thanks to its rapid growth and ability to spread. Culturally it has been used to make all kinds of artifacts, furniture and constructions since ancient times. In pre-Hispanic times, small controlled burns were made to let this species in and to make the undergrowth more lush, according to Luis Otero and other researchers dedicated to studying the cultural influence of quila in the history of fire. At the same time, this interaction that the species has with its environment, came to be frowned upon in later times, when agriculture emerged massively, because by flowering and drying (in periods that have no proven regularity), it brought bad omens for people, such as plagues of long-tailed mice (linked to the anta virus) and socio-natural catastrophes. It is often linked to fires, because after the quila blooms, it dries up and remains as available fuel material in the forest.

Colihue in Bosque Pehuén.

In reference to the narration of one of the residents of the "Ecologies of Fire" cycle, where she tells us that after some forest fires, many nutrients rise and become available for plants that want to establish themselves after the fire. Sebastián Carrasco of FMA explains that the fire and the species that follow it help these nutrients to "rise" and thus the plants can consume them more easily. This is called the intermediate disturbance hypothesis. This refers to the fact that the passage of fire, seen as a disturbance at intermediate intensities, can explain the diversity of species in certain ecosystems. Conversely, ecosystems with very low disturbances or very high disturbances have less richness and abundance and are less diverse, and therefore less resilient. This gives us clues about the adaptive capacity of some species in the Andean Araucanía, their evolution and change as the only constant, where the balance with the presence of fire is presented as a protective factor.

Sebastian Carrasco draws a diagram of fire ecology on the ground.

One of these species adapted to fire episodes is the araucaria (Araucaria araucana) or pewen in the Mapuche language, considered a sacred tree for the Pewenche culture and also a tree species declared a National Monument in Chile. The araucaria has coexisted with fire for thousands of years. It has a hard bark and is able to resist the passage of fire, because it has been living around the abundant volcanoes that make up the Andean geography. Pamela tells us that when they visited the China Muerta National Reserve, the landscape was overwhelming because everything was burned. This forest reserve suffered a large fire in 2015, where official figures indicate that, according to CONAF, 3,675 hectares were affected, and 2,900 hectares, according to the Satellite Remote Sensing Laboratory of the University of La Frontera, of which 1,550 were located in the China Muerta National Reserve and almost half of this area is occupied by araucaria forests. From afar, the landscape was tremendous, desolate, however, as she approached, she told us that she felt that it was not so Dantesque or apocalyptic, because she could see that there were araucaria sprouts everywhere, even some coming out of completely burned trees, usually called "dead standing". These trees represent a tremendous value of biocultural memory, since they are not only biological legacies for their own species and other organisms that are born or develop in them, but also cultural legacies, since they speak to us of other moments and events, being a source of access to an ancient temporality, of ancestral landscapes.

The araucania trees, also called 'pewen' in Mapudungun and 'monkey puzzle' in English.

However, as we travel through these landscapes through walks, memories and narratives, a question arises that worries the residents: What happens when we move the fire to the Central Valley of Chile, in areas with species and settlements that are not necessarily accustomed or adapted to receive this disturbance? When this fire is tremendously intense and devastates everything, how do we recover from it afterwards?

An araucania tree that was struck by lightning.

An article by Moritz and co-authors indicates that fire differs from other hazards in that, in this case, the focus is more on fighting them and how the command and control approach typically used in fire management neglects the fundamental role of fire events in maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem services. Thus, this aspect is key for us, as there is not much research in this area. While in these conversations we come closer to understanding that it is not just about command and control, but about how to learn to coexist with fires. Therefore, we asked ourselves what types of social organization or environmental design are most beneficial for fire management? Since we understand that understandings of fire change in relation to scale, also at the level of plants, interactions between organisms, landscapes, cultures, towns or cities. Thus, we believe that the scale and perspective of fire is something yet to be investigated.

As the residents of "Ecologies of Fire" shared with us, we can understand how, from a vision solely focused on territorial planning and the satellite panoramic of physical landscapes, fire or fires, with the social charge that this word contains, can be seen as plagues. Also, from other visions and cosmovisions, we manage to understand that, at other times, these fires can be understood as a manifestation of fire that favors the balance of nature. So, for us this connection is interesting, because we can understand why when we say "we are plagued by forest fires in Chile" we are reducing too much the analysis of a socio-natural conflict, which may well be a great opportunity to question our relationship with nature and its elements.

However, the stories about the way in which fire relates to different ecosystems and human settlements gradually led us to the need to distinguish the effects of fires on forests, characterized by the presence of biodiversity, whether they are composed of endemic, native or exotic species. Compared to the effect of fires on monoculture tree plantations, extensively present in Chile, where approximately 60% of this area corresponds to radiata pine, 33% to species of the eucalyptus genus and the rest to other species such as Atriplex, tamarugo and Oregon pine. These plantations are located mainly between the O'Higgins and Los Lagos regions. According to Conaf statistics, in the period 2010-2022 forest plantations have been the main type of vegetation affected by fires (at an average of 44,000 hectares per year), representing 40% of the total area burned (compared to 17% for native forests). In the decade 1990-1999, forest plantation fires affected 10,000 hectares per year, which corresponded to 20% of the total burned area. Therefore, we are strongly surprised that even institutions such as Conaf, call these plantations forests, since we see how they lack a constitutive element of these, which is biodiversity and homogenization of the landscape, which is ultimately one of the key factors in the spread of fires. This allows not only the resistance to the effects of fire, its propagation, intensity and frequency, but also allows the regeneration of these ecosystems, once affected by fires.

Valeria shares with us her concern about human intentionality in forest fires, considering not only the fact of how the fire starts, but also the way in which landscapes have been manipulated in Chile, where forest plantations have gained more and more territorial extensions. With high densities and little oversight by the relevant authorities regarding their management practices, which must adhere to a legality that is already quite permissive in this regard. According to her, this highlights the fact that the problem does not necessarily arise from the species used in monocultures, but rather from human practices in monocultures, weakening ecosystems and generating landscapes that are highly prone to destructive forest fires.

This conversation evokes a phrase spread by geographer Jorge Felez-Bernal, researcher associated with the Environmental Sciences Center EULA-CHILE and Faculty of Environmental Sciences of the University of Concepción, where he points out that "Chile is a country configured for disaster", referring to forest fires. This is where Valeria's concern arises, as she feels a great responsibility and commitment to share the findings of the research in which she works, since she sees a disconnection between the development of science in this aspect, people's education and, therefore, their degree of responsibility and involvement in this issue. One of the ways to connect these aspects that the experience of "Ecologies of Fire" has allowed her are artistic elements such as fiction, which can be used to tell stories from other perspectives, for example, from the perspective of the trees when they are affected by fires and by the destruction that humans produce in their ecosystems. In this way, becoming aware of other living beings involved in human actions and, from there, building more respectful ways of relating to the otherness of these beings.

A grove of Nothofagus (Coihue) in Bosque Pehuén.

Fire cultures

In what we know today as Chile, there is not only a great territorial, geographic and ecosystemic diversity, but also a great cultural diversity. A living proof of this are the different native or indigenous peoples that have inhabited this territory and coexisted with its elements for hundreds, even thousands of years. As we walk and enter this forest of stories, we begin to wonder about the way in which cultural practices on fire and fires interact with the landscapes and how these cultural practices could or should be modeled to face our current problems.

Pamela tells us that she lives next to a monoculture tree plantation. As a family, they usually do controlled burns, which is beneficial for them because it allows them to coexist with these plantations. But when she was able to experience the relationship with the forest in the FMA reserve, she felt that the relationship with fire was different. She believed that it was almost impossible for this forest to catch fire, because of the moisture it contains. However, when she heard stories of past fires in Bosque Pehuén, which was formerly a logging ranch and had episodes of intentional and natural fires, she experienced other languages and components outside of fire as something destructive, because she felt that in the forest a harmonic dynamic was being maintained between fire as the original element of life with a spirit that inhabits it, the ngen-kvtral in Mapudungun, and the mawiza or mountain, in the same Mapuche language.

Thus, as in the original myth about the first Mapuche weaver, which Pamela uses as a starting point for her artistic research, fire as a vital and spiritual element plays a key role in reuniting that girl with the ancient spider that will teach her to weave. In the same way, she sees that the experience in the "Ecologies of Fire" residency was an instance where fire brought them together as women, both materially, around the fireplace and the wood stove, and conceptually, through their artistic and scientific explorations. The weaving of this collaborative network allowed them to gain new perspectives and learn new practices and habits around fire as a relational element. This motivated them to co-create a collaborative recipe book, which they produced and exhibited collectively, along with their research.

The field school group investigates the teachings of fire.

We note how this practice of gathering around the fire to sustain vital aspects such as heat and food in a home, are extensive in La Araucanía, as well as in other regions of southern Chile. The book "Guardianas del calor: mujeres y el cuidado del calor de hogar", compiles a series of stories, with the objective of valuing, understanding and learning from the strategies and experiences exercised by women to take care of the heat in their homes during the cold seasons in conditions of vulnerability related to social housing, where most of the problems of energy inefficiency are concentrated. According to the information compiled in this book, the low temperatures inside homes in southern Chile are the result of two main factors. First, the economic limitations of households to generate the necessary heat, either for lack of resources to pay for heating or access to appropriate technologies. And, secondly, that homes lack adequate thermal insulation, and most buildings do not meet any thermal quality standards that would allow them to cope with the climatic conditions of these latitudes. For this reason, in the central and southern regions of Chile, we face a generalized problem, what the authors call heat deprivation. Heat deprivation shapes the life experience of energy poverty, impacting the daily life of people, their overall health and strongly affects their decisions regarding the responsible use of fire.

Lentil soup and fire for cooking.

Maya Errázuriz, from FMA, tells us that she was recently able to visit the Magallanes Region, where she learned that research has been conducted in Tierra del Fuego, in relation to ancestral fire practices, where they spoke of cultural marks on tree trunks, associated with the use of fire by the inhabitants of the Kaweskar people, called Fuegians by the settlers. The Kaweskar are a native people of southern Chile and Argentina. Until the middle of the 20th century they were nomads who traveled in canoes through the southern channels of western Patagonia, between the Gulf of Penas and the Strait of Magellan. In the last century, their population was reduced by massacres and deaths due to disease, as well as abandonment of their groups of origin. The practice studied consisted of burning certain parts of the trunk to extract a piece of the bark without the need to fell the tree and, in this way, generate the canoes on which their subsistence depended. These marks remain in time, in those trees that remain alive. And when dendrochronology studies are carried out on them, those points of cultural intervention are marked, which are called cultural marks related to fires. Although it is necessary to explore aspects such as the frequency and intensity of these practices, the fire culture of the Kaweskar is interesting to us, since the families lived in canoes all the time and kept a fire burning in the center of the canoe for heating and cooking. How fire was a key element for survival in such a challenging ecosystem.

This relationship with fire, from the everyday and vital, gives us clues for a new understanding of fires, understanding them as a manifestation of fire that is in constant relationship with other processes, both natural and social. This new and necessary understanding tells us about fire as a relational system that transforms and brings together, but that can also become unbalanced and extremely destructive and dangerous. At this point in our journey, we wonder how we can approach these different and sometimes so distant perspectives on fire, to understand them and make them part of our practices. For by understanding it as a separate element, we run the risk of not dimensioning its influence on what surrounds us.

We reflect that, as with other relational systems in nature, we need to experiment with fire to learn to relate to it in a balanced way. By seeing it as a lifeless element, separate from others or as an object, we dissociate ourselves from its behavior and do not care about keeping it alive and caring for it. In a world where access to experience with and in nature remains unequal, it is challenging to spread this understanding. However, ancestral wisdom, immersed in our cultural practices, provides us with opportunities to reconnect with the need to feel fire as something of our own, constitutive of our subjectivity and, therefore, of our way of relating to our environment. This ancestral wisdom invites us to be part of the relational system of fire and its community, so that, as communities, we learn to be more resilient in the face of the socio-natural disasters that forest fires may or may not become.

The field school group investigates the teachings of fire.

Signs of fire in the forest

As we begin to look for signs of fire on our walk through Bosque Pehuén, Sebastián Carrasco of FMA tells us that much of the living forest we can see is quite young, as the species at lower altitudes must be no more than 40 years old, as a result of logging and fires in recent history. However, it is possible to recognize the histories of this ecosystem thanks to the signs of fire. In order to perceive these signs of fire in the forest, we asked the residents what sensory tools had allowed them to expand their notions of fire, or to delve deeper into their research. We talked about what the environment gives them, approaching it through sound, texture, image, and how this changes the way they relate to the forest. This approach allowed us to look for ways to contribute to fire and fire education.

Barbara wanted to start with what she considered the most basic, before highlighting any practice or technique. And it is related to the experience of walks in the forest, where a set of impressions arise, walking and breathing in a space, observing, touching, all that set of sensory impressions. By the simple fact of changing the format of reception of the information that she usually has in other places. Because, like Fernanda, she lives in the city, where she is used to consuming information through screens and audiovisual elements, which is very smooth, very sterile. So, only by changing this predisposition to see and observe in another way, it became a key element. For her part, Gianna comments that one of the things that has most caught her attention is the temperature. How with the temperature changes we have experienced, when they go to the forest, their body temperature changes. This has allowed her to understand the forest as an other, with its own body temperature.

Remains of burned wood from past land management practices.

Something similar happened to Valeria, especially when they had the immersive experience with Agencia de Borde, because it involved entering a forest and looking at it with other sensors, corporeal sensors, such as temperature. And you realized that by being in clothes you are most likely not reading, feeling and sensing everything around you. Even the sense that the rocks have in the feet or also the fear of touch, the sound of the wind, mainly the Puelche. They are different winds, they move differently and he could also feel how they moved. In that sense, he understood that his body is also a sensor and that it is able to perceive certain changes in temperature and atmosphere. Perhaps the body as a sensor has been the most interesting thing for someone like her, who is not used to understanding the world from her skin, from her touch, from how she sees and smells. She is usually aware of how to geolocate events, as part of her job. However, approaching the forest from that immersive scale was quite different, and changed many of her reflections.

Charcoal fragments from a burned tree.

This idea of the body as a sensor is key for us in a hyper-technologized world, but with unequal access to an overproduction of digital data, as it seems that for science data is never enough and there are always more unknowns. In this context, the body as a sensor is an opportunity to reconnect with that which is most characteristic of human beings, which we share with other animals, as part of nature. But also as an opportunity to approach those people who cannot have access to digital sensors, in order to experience nature or the environment. In that sense, the body as a sensor is a democratic medium, because anyone can access to use it, with the right conditions, learning or guidance. In the same way, this body sensor allows us to learn to read the behavior of the landscape, which is key when facing the presence of fire or a fire.

Hike during the field school in Bosque Pehuén.

Recalling one of the conversations they had with Fernanda, director of Corporación Altos de Cantillana, the residents commented on how difficult it is to predict how the fire will advance in a forest fire. Especially when considering how climate change and changes in landscapes have changed the behavior of winds. It is therefore necessary for us to relearn how to read the landscape in order to prevent forest fires or to better relate to nature. This is also related to the fact that fires can generate their own climatic conditions. In this regard, there is research, such as that of Alvaro Gonzalez, professor at the Universidad Austral de Chile (UACH), which shows that no matter how many combat elements are available to face an uncontrolled forest fire, these usually only help to appease it or to direct its advance, but most of the fires of large extensions or mega forest fires, usually end up being extinguished by their own conditions, which has been called firestorms. In view of this, the difficulty to predict the occurrence and advance of forest fires is increasing.

In this context, the need to learn to experiment with nature and its elements, as relational systems, becomes key to advance towards the care of ecosystems and human life. When Pamela told us that she has been able to identify a "mother tree" within Bosque Pehuén and has returned to visit it daily during her residency, it became evident to us the importance of becoming aware of the exercise of signifying the elements of our environment, in order to feel intimately involved with them. The sensation that the forest is constantly changing and that, at the same time, we are so small in the face of its processes, requires that signification to give meaning to our existence within these transformations. Environmental psychology has been dedicated to understanding the role of behavioral and mental factors involved in the relationship between humans and nature. Thanks to this, we have been able to understand that the positive valuation of nature and the involvement with its care are directly related to the possibility of experimenting with and in it. However, it seemed important to us to distinguish that the relationship we experience and establish with nature should be based on exploration and coexistence in order to learn to coexist. Not from dominance, since this hierarchical position towards natural elements is part of the modern worldview that has led us to its commodification and destruction.

Charcoal fragments from a burned tree.

Finally, after sharing many experiences and reflections, we returned from our hike to the refuge to have lunch together, digest feelings and ideas, and have a relaxed conversation about the key points in fire research, experiences, stories and cultures. We were able to take some of these reflections to the next day's Field School in Temuco, where we specifically addressed how to develop community plans to prevent or react to forest fires.